Modern light sources are rated in lumens or, more importantly, lumens per watt. The first figure expresses the brightness of the source whereas the second indicates its efficiency. But what, exactly, is a lumen?

To answer that question it is useful to recall that the first man-made light sources relied on heat and were very inefficient in terms of transferring energy for illumination. The discovery of electricity made possible a variety of new methods for generating light that didn’t rely on heat. Discharge and fluorescent lighting are two such methods. Discharge tubes emit a dominant colour whereas fluorescent tubes produce light that looks visually “white”. No further details will be given here as the principles behind these two types of lighting have been explained previously in some depth. For more information see https://physbang.com/2024/02/12/discharge-and-fluorescent-lighting/.

The first electrical light sources for domestic use were incandescent lamps (hot light bulbs) developed by Joseph Swan in England and Thomas Edison in America. It is likely that Swan was the true inventor (during the period between 1860 and 1880) but it was Edison who patented an improved product, not only in America (in 1880) but also in England. There is more about this on the website of The Institution of Engineering and Technology, at https://www.theiet.org/membership/library-and-archives/the-iet-archives/biographies/joseph-swan.

Incandescent lamps work by passing an electric current through a thin filament. The filament glows white-hot and produces a balanced spectrum of light but only as a by-product of generating heat. When such lamps were the only type of domestic lighting, it was acceptable to talk about the brightness of a light source in terms of its electrical power consumption; a 60 W lamp was considered normal for short-range use whereas 100 W lamps were commonly used for whole-room lighting.

Other forms of lighting, such as LED lamps, can produce the same amount of light from less electrical input so the idea of measuring brightness simply in terms of electrical wattage is no longer meaningful.

To describe the performance of a light source more accurately, we need a scale that specifically measures the amount of light emitted. Sadly, light sources can emit a wide range of wavelengths and it would be wrong to treat all wavelengths equally when the human eye can see only a very narrow range, which is typically given as about 380 – 760 nm. So we need a measurement unit that takes account of the light emitted from a source in terms of the brightness perceived by the human eye.

The lumen (lm) is the SI unit of luminous flux: it quantifies how much visible light is radiated from a source in all directions. Importantly, the luminous flux from different light sources is best measured rather than calculated as it depends on a variety of variables.

To complicate matters, most light sources do not illuminate in all directions so it is better to use luminous intensity, with the SI unit of candela (cd), where one candela is equal to one lumen per unit of solid angle (one steradian). Incidentally, the candela is the only SI base unit that is determined with reference to human characteristics (visual perception).

It follows that candelas are linked to lumens via the beam angle of the light source: a narrow beam from a low-lumens source can be brighter than a high-lumens floodlight. There is a good discussion of this on the website of portable lighting specialist O-Light, at https://www.olight.com/blog/candela-vs-lumen-what-is-difference.

Although the candela is one of the seven SI base units, it is not ideally suited to practical applications, where light sources have a finite size and surfaces are usually flat rather than sections of spheres. We therefore have a second unit for luminous intensity, which measures the illumination incident on a two-dimensional area: one lumen illuminating one square-metre is equal to a luminous intensity of one lux.

The maximum theoretical output of a light source is 683 lumens-per-watt but that can only be achieved using monochromatic light with a frequency of 540 x 1012 Hz. This relates back to the lumen being defined in terms of human visual perception, which peaks at a yellow-green colour of wavelength 555 nm, equal to 540 x 1012 Hz. Unfortunately, monochromatic lighting is not suitable for general illumination as objects cannot reflect the full range of wavelengths required to display their natural colours.

Broad-spectrum light sources typically achieve little better than 100 lumens-per-watt and even the best only nudge above 200 lm/W. According to UC San Diego physics professor Tom Murphy, writing in 2011, “the most perfectly engineered light that we would perceive as ‘white’ cannot achieve much more than about 250 lm/W” (https://tmurphy.physics.ucsd.edu/papers/lumens-per-watt.pdf).

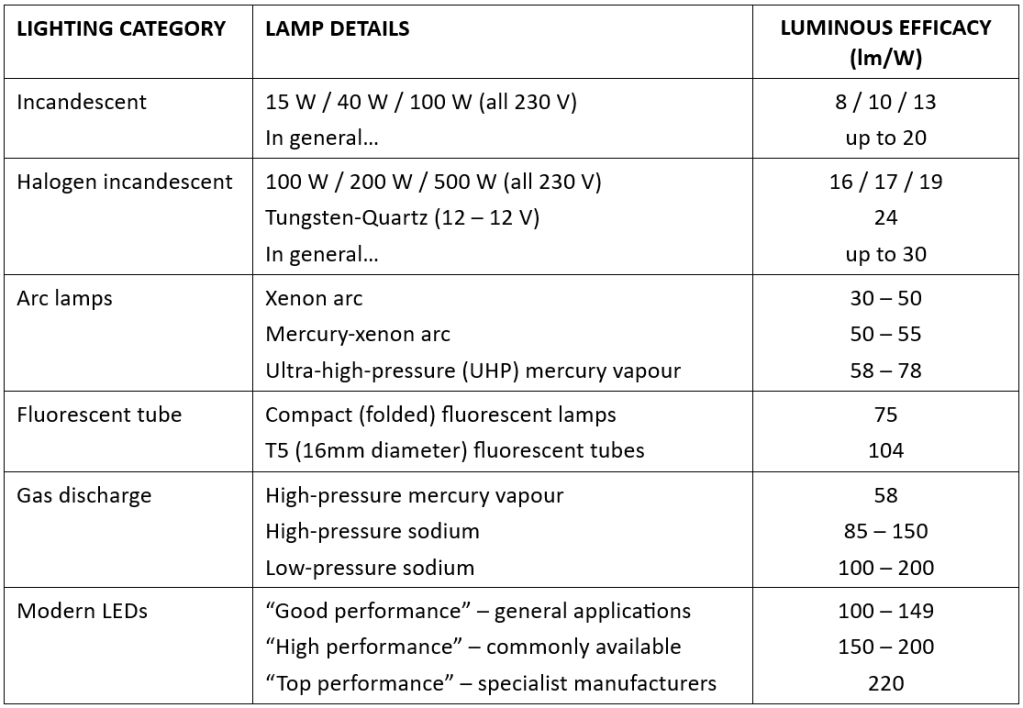

Although lumens-per-watt sounds like an efficiency figure, it is not a true efficiency as it is not stated as a percentage. The correct term is for lumens-per-watt is luminous efficacy. Appropriate figures for different types of light sources are compared in the table below which contains information taken from the websites of LED specialists LEDrise and TriLux.

Further reading: It is worth exploring other pages on the LEDrise blog and within TriLux’s knowledge centre. In addition, another LED specialist, Emilum, has some useful diagrams illustrating the various measurement units that have been discussed in this article (https://www.emilum.com/en/blog/knowledge/units-of-light/) and there is a less technical summary on the Setick home-information website (https://www.setick.com/what-is-lamp-efficiency/). For those who want more detail rather than less, there are some excellent in-depth explanations about various aspects of photonics, including photometry, in RP-Photonics’ online encyclopedia (https://www.rp-photonics.com/photometry.html).

One thought on “What are lumens?”