It is tempting to regard the equations for electric fields and electric potentials as being separate things but they are so closely related that they are best viewed as different sides of the same coin. This is because electric field strength is the same as potential gradient. Or to put it another way, the electric field determines the rate of change of the electric potential.

For the case of a uniform electric field, between parallel plates, the potential increases linearly from the negative (zero potential) plate to the positive plate: in the same situation, the electric field strength has a single constant value, which is equal to the gradient of the linearly-increasing potential. The electric field is therefore the same as the potential gradient (except for the fact that it is in the opposite direction, as will be explained shortly).

For the case of a non-uniform electric field due to a spherical charge, the potential at a location within the field is equal to the work done when a test charge is brought “from infinity” to the stated location. Given that the field strength varies as the inverse-square of distance, the total change in potential will be an integration of the different field strength values that exist over the relevant path. If the relationship between field strength and distance is plotted as a graph, the change in potential between two points will be the area between the curve and the distance (x) axis.

In the same way that the value of the electric field is given by the rate of change of potential with distance (the potential gradient) so the change in potential is given by the integral of the electric field strength between the two points being considered. The only refinement required is that the electric field strength is actually the negative gradient of the potential because the field is defined by its force on a unit positive charge and the potential gradient increases from zero towards a positive voltage (which repels the positive test charge).

Note that it is important to distinguish between the (absolute) potential that refers to the work done when a charge brought “from infinity” versus the change in potential due to the movement of a charge between two locations that are separated by a finite distance.

The potential fields around positive charges always have positive values and decrease to zero, indicating that a repulsive force will act on any positive test charge that is within such a field. Conversely, the potential fields around negative charges always have negative values and rise to zero, indicating an attractive force acting on a positive test charge.

All of this information is covered in a presentation that can be downloaded here as a pdf file.

When I recently delivered this presentation to one of my classes, a particularly alert student asked for the basis on which the distance in a uniform field can be cancelled against one of the radius terms in a spherical field (as shown in Slide 7). The honest answer is that this is not correct and at most I should have said it is “as if” the terms can be cancelled, given that they both relate to distances inside electric fields.

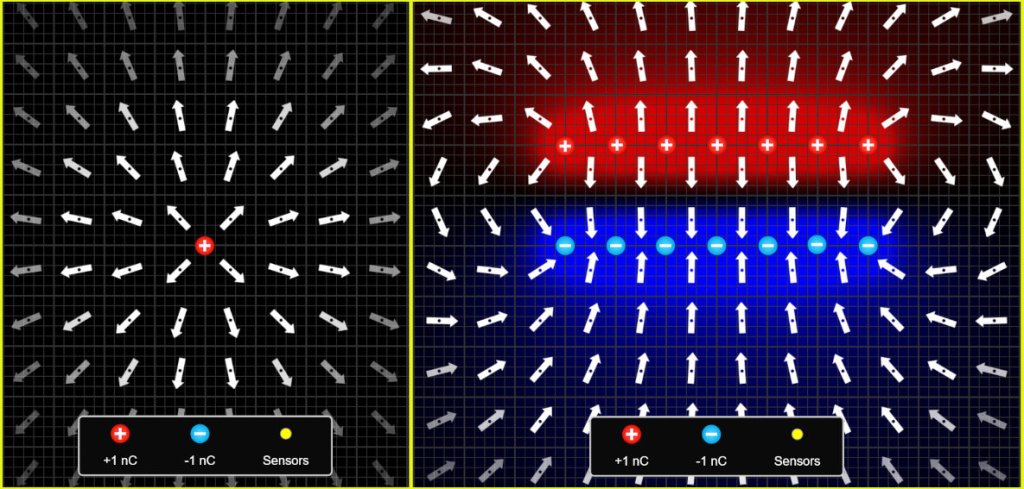

Some justification for that general statement can be found by considering a uniform parallel-plate field as being due to rows (planes) of multiple spherical charges that are positioned close together. This is illustrated in the diagrams below, which were created using the PhET Charges and Fields simulation (https://phet.colorado.edu/sims/html/charges-and-fields/latest/charges-and-fields_all.html).

In graphical terms this suggests a degree of equivalence but the spherical-charge equation applies to an isolated body so the combined effect due to multiple charges is not valid except as a tactic to link the two different situations in a broadly descriptive manner.

The only rigorous answer to the student’s question is to use a more thorough approach to the potential gradient and treat it as a differential that can be converted into the appropriate field equation by integration. This not only results in the correct form of the potential equation but also incorporates the negative sign required to ensure that opposite charges produce an attractive force and to maintain consistency with the difference in direction between the potential gradient and the electric field.

For completeness, I have also added a pdf version of a shorter follow-on presentation looking at equipotentials, which can be downloaded here.