To conclude the recent series of posts related to different aspects of motion, we will now look at a real-world application of these ideas: in particular, the physics of slowing and stopping a road vehicle. An earlier post (from 2019) covered the two components of a vehicle’s overall stopping distance so I won’t repeat that here: instead I recommend that you read the Stopping Distance article separately.

In today’s article, we will go on to explain braking by looking at the transfer of kinetic energy.

The quickest way to slow-down a car or bicycle is to apply the brakes. Given that the braking system is part of the vehicle, it’s easy to miss the fact that a moving object cannot change its motion unless it interacts with the external environment (as required by Newton’s First Law of Motion).

To make things clearer, let’s think about slowing a bicycle by putting your feet on the ground and using the friction between your shoes and the road surface. This action converts kinetic energy into heat and mechanical deformation of your shoes (they get scuffed) and that transfer of energy is what causes the bicycle’s speed to decrease.

In cars, excluding The Flintstones cartoons, there is no option to “put your feet down” and most braking involves transferring kinetic energy as thermal energy, which can cause the brake disks to glow under very hard braking.

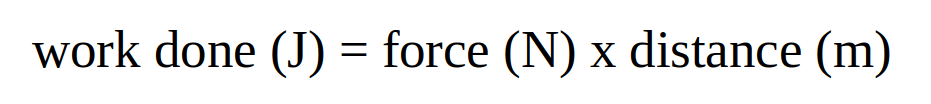

Braking is effective because work is done (energy is transferred) whenever a force is moved: the work done is equal to the product of the force and the distance through which it moves;

A vehicle’s kinetic energy reduces by the same amount as the work done in braking. This means the vehicle will come to a stop when the work done in braking is equal to the vehicle’s original kinetic energy. We can balance these two equations against each other, as follows;

This explains the comment made in the Stopping Distances post, where the following is stated; “If the mass of a vehicle is doubled then the braking distance will be doubled. But if the speed of the vehicle is doubled, the braking distance will be quadrupled.”

The same principle applies for brake systems that are entirely within a road vehicle, except that there is a further complication because the tyres have to maintain their grip with the road during braking. If the tyres lose grip then the vehicle will skid. This changes (reduces) the braking effect. It is a harsh fact that when a vehicle skids, it loses speed more slowly and a crash becomes more likely.

When there is controlled braking, the friction that causes the vehicle to slow down happens within the braking system, causing the brakes to heat-up as the vehicle’s kinetic energy reduces. But when there is a skid, the brakes are locked and there is no friction in that system: the only friction that will slow a skidding vehicle is external to the vehicle, between the tyres and the road surface. The friction between the tyres and the road is a smaller force than can be achieved inside the brakes. This means a skidding vehicle will cover more distance before it comes to a halt.

The equations above and charts printed in the Highway Code (see below) clearly indicate that a small increase in speed will give a big increase in stopping distance. This is a key fact that you must remember both for GCSE examinations and when driving in real life.

Stopping distances also increase when the road has a slippery surface or the vehicle’s tyres are worn. So drive slowly when there is ice or gravel on the road surface and replace your tyres before their tread reaches the minimum legal depth.

Footnote: For completeness, I should add that electric vehicles with regenerative braking transfer a significant proportion of their kinetic energy as useful electrical energy, which can be returned to the vehicle’s battery for storage (chemically) and reuse later.