Heating a substance can cause either an increase in temperature or a change of state. This is not completely obvious, so let me put it another way; sometimes when we “heat up” a substance it doesn’t actually get any hotter. The reason for this is that the energy supplied is being used to break bonds within the substance, allowing it to change from a solid to a liquid or from a liquid to a gas. And while this is happening, the temperature of the substance stays constant.

At other times, we have the more familiar situation where the energy given to a substance causes its temperature to rise. But how fast does it rise?

If we supply the same amount of energy to two different substances, let’s say a block of copper and a block of iron, do the two blocks increase by the same temperature? To make this a fair test, the blocks will have the same mass and the same insulation. Despite this, the two blocks will in fact increase their temperatures by different amounts.

Every substance has its own number that allows us to predict the temperature rise for every joule of energy that is transferred to a fixed mass of that substance (assuming that there is no change of state). This property is called specific heat capacity.

Water, for example, has a specific heat capacity of approximately 4200 J / kg °C. This means that to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 °C we must provide 4200 J of energy.

Similarly, it we wanted to raise the temperature of 5 kg of water by 10 °C then we would need to provide 5 x 10 x 4200 J of energy (210 000 J).

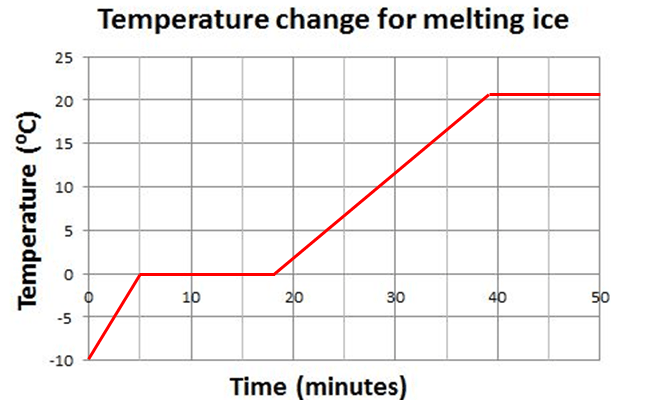

The specific heat capacity of a substance is effectively the gradient of the sloped section on those familiar heating graphs that you have seen on several occasion, similar to the example below.

You will notice that the gradients of the two sloping sections are different: this tells you that the specific heat capacity for H2O has a very different value for water compared with the value for ice. The actual values are listed below, together with the value for steam (which is similar to ice).

- specific heat capacity of ice: 2100 J / kg °C

- specific heat capacity of water: 4200 J / kg °C

- specific heat capacity of steam: 2000 J / kg °C

NOTE: You do not need to learn the values given above – although it would be useful to know the approximate value for water as it’s such a common substance and is also vital for life on Earth. If you are interested, you can read a short and simple summary about the climatic importance of water’s high specific heat capacity on the US Geological Survey website, here.

There is a standard experiment to investigate the specific heat capacity of different substances. The experiment uses an electric heater to provide energy that can be measured using values for the current, potential difference (voltage) and time. These values are entered into the equation;

Energy supplied (J) = current (A) x voltage (V) x time (s)

This is then used to find the specific heat capacity via the equation;

Energy received (J) = mass (kg) x temperature increase (°C) x specific heat capacity (J/kg °C)

BBC Bitesize has two explanations about the required practical to investigate specific heat capacity; one is for the Edexcel Physics course and the other is for the AQA Trilogy course – but it’s worth reading both regardless of which course you are studying.

There is also my own one-page summary handout, which you can download here.

Finally, if you want to see how widely values for specific heat capacity can vary, and maybe try to spot some patterns in the values, then take a look at the table on The Engineering Toolbox.

One thought on “Specific Heat Capacity”