Having looked at some of the finer details for beta decay in two previous posts (Q-Value and Metastable Nuclei) it seems fitting to round-off this short series with two phenomena that involve orbiting electrons rather than just nucleons.

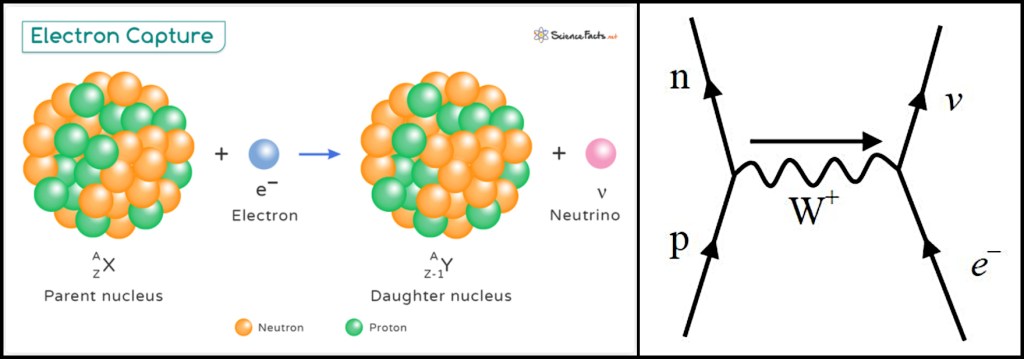

The first effect is electron capture. As its name suggests, this is when an orbiting electron is captured by the nucleus, resulting in a proton transforming into a neutron. Normally proton-to-neutron conversion would be achieved by emitting a positron but positrons are antimatter particles that are formed in pair-creation events with their equivalent matter particles (conventional electrons). In order for positron emission to be viable, the energy difference between the parent and daughter nuclei must exceed the rest-mass energy of the particle pair. If the energy difference is less than this, beta-plus decay cannot occur and electron capture provides an alternative route for reducing the number of protons in the nucleus.

At first sight, this mechanism seems like a step backwards in physics theory as it implies the ability of a positive nucleus to attract a negative electron by the action of an electrostatic force. That in turn seems to suggest all orbiting electrons should be able to accelerate into the nucleus but we know this does not happen. The apparent contradiction is explained by realising the mechanism at work is not electrostatic attraction: it is actually due to the wave nature of electrons.

Thinking of electrons as waves, there is a finite probability that an orbiting electron could find itself inside the nucleus and if that were to happen then the electron could be retained through a weak interaction, causing a neutrino to be emitted.

The orbiting electron that is captured would most logically come from the K shell, because those are the electrons closest to the nucleus, but L-shell (second-closest) capture is also possible.

Electron capture produces a –1 change in the proton number with no change in the nucleon number (atomic mass). The daughter nucleus recoils to balance the momentum of the emitted neutrino, which is very hard to detect by any direct means. The hole left by the captured electron will be filled by a further-out orbiting electron, accompanied by the emission of one or more x-ray photons with specific energies depending on how many electrons, and which ones, are involved in the cascading process.

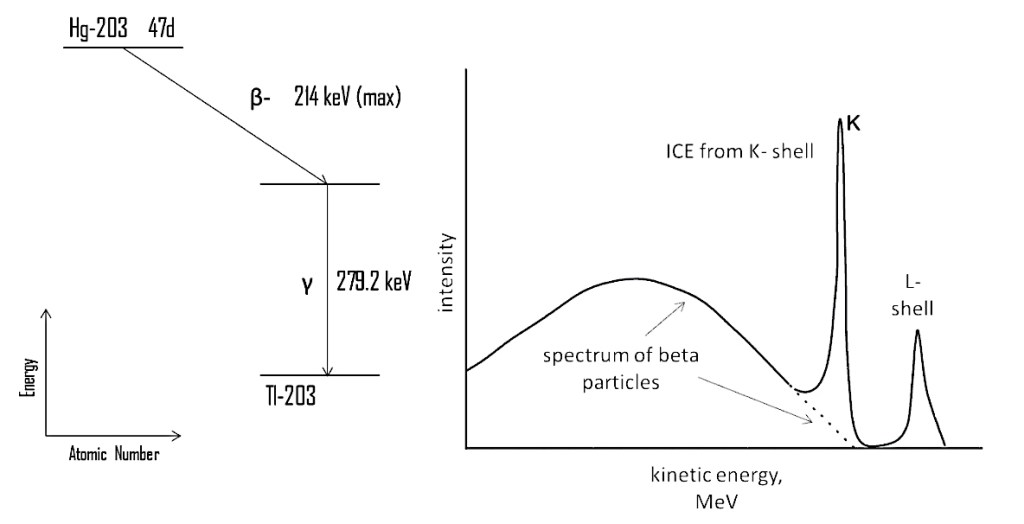

Internal conversion also involves the orbiting electrons but in this case an electron is expelled from the atom rather than being captured by the nucleus. The starting point for internal conversion is a daughter nucleus that exists in an excited state after a previous decay mechanism (which can include electron capture).

As with electron capture, the wave function of the electron allows it to interact with the nucleus but the internal conversion process results in energy being transferred to the electron rather than the electron “combining” with a proton. The excess nuclear energy that is transferred allows the electron to escape from the atom entirely. There is no change to the atom’s proton and nucleon numbers: this mechanism is just a way for the nucleus to drop to a more stable, lower-energy state. Once again, the hole left in the inner electron shell is filled by an outer electron, accompanied by the emission of one or more x-ray photons.

The electrons that are emitted through internal conversion are not “beta” electrons as they were not produced by a weak interaction but their emissions do appear as spikes overlaid on the beta energy spectrum. (They are spikes because the energy changes they represent in the nucleus are quantised, just as the accompanying x-rays have specific energy values because transitions within the electron orbits to fill the K-shell gap are also quantised.)

One thought on “Electron Capture and Internal Conversion”