Having recently posted a general piece about spin in general (https://physbang.com/2024/11/24/what-is-spin/) I thought it would be useful to discuss one particular use of spin in a practical context; cooling.

Suppose we have a material with a single unpaired electron in each of its atoms. The lone electrons can either be spin-up or spin-down and on average there should be similar numbers of each spread across the quadrillions of atoms in the sample.

Now imagine that we apply a magnetic field to the sample: the lone electrons whose spin (magnetic moment) aligns with the field will be in a lower energy state than those whose spin is opposed to the field. As a result, some of the opposite-spin electrons will flip to align with the applied magnetic field. If the magnetic field is then switched-off, the electrons will return to a random distribution of spin-up and spin-down.

This is fairly straightforward but there is a thermal side to all of this as well. Firstly, the difference in population between spin-up and spin-down electrons is dependent on the temperature of the sample. More importantly, when the atoms are magentised, the resulting spin-flips radiate thermal energy and when the magnetic field is reduced to zero the ambient temperature allows the electrons to resume their random distribution of spin orientations.

Now let’s combine these two components by allowing heat to escape when the electrons are magnetised but applying perfect thermal insulation when the field is switched off. As the electrons return to a more random arrangement, without the input of external heat, the sample will undergo internal cooling due to the link between entropy (randomness) and temperature.

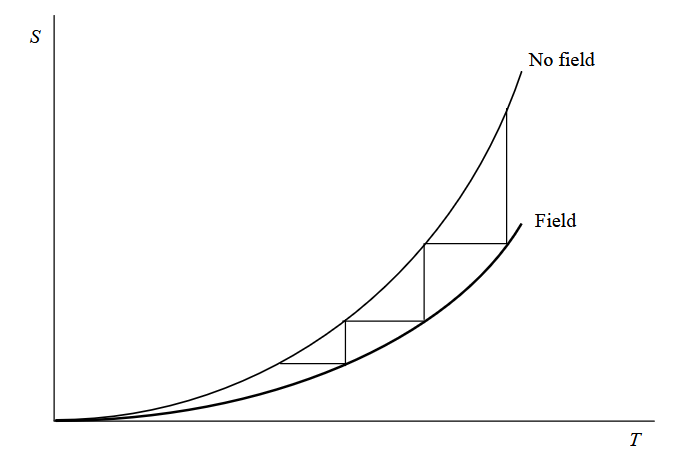

Having cooled the sample, we can then repeat the process by reapplying the magnetic field and remove the insulation to allow the heat to escape before demagnetising the sample in thermal isolation. It would be nice to think we could do this as many times as necessary until the sample eventually reaches absolute zero. But is that actually possible?

Unfortunately, the answer is a firm “no” because the effect of each cycle gets smaller as the temperature gets closer and closer to absolute zero. It is rather like the idea of walking towards a distant point by halving the remaining distance with each step. Using this method, you would never reach your destination despite constantly making progress towards it.

In thermodynamics there is an important rule that says it is impossible to reach absolute zero by repeating a finite number of cyclic steps (in this case, isothermal magnetisation followed by adiabatic demagnetisation). This rule is in fact the Third Law of Thermodynamics. Therefore, although spin cooling is a real effect that can generate very low (milli-kelvin) temperatures, it doesn’t provide a means by which to achieve absolute zero itself.

Incidentally, the rule that we cannot reach absolute zero from a positive temperature also allows the possibility that there may be a “mirror” condition that forbids reaching absolute zero from a negative temperature. This is a fascinating proposition that is brilliantly explained in Peter Atkins’ Four Laws That Drive the Universe. I thoroughly recommend this short book (just 130 pages) to anybody who wants to find out more. Also well worth studying is the free online course in Heat and Thermodynamics written by Dr J B Tatum, which is available online at https://www.astro.uvic.ca/~tatum/thermod.html