Most exoplanets (planets that are outside the Solar System) are detected indirectly. Either a temporary and regular dimming is measured as they pass in front of the host star or their orbit causes a wobble that produces a periodic red-shift in the star’s spectrum.

Only a small number of planets have then gone on to be imaged using the light they emit by virtue of their surface temperature. Effectively, this is like using an infrared camera to see people in the dark – except that in this case the emitting object is located very close to a much brighter object (the host star) that nearly drowns the tell-tale signal.

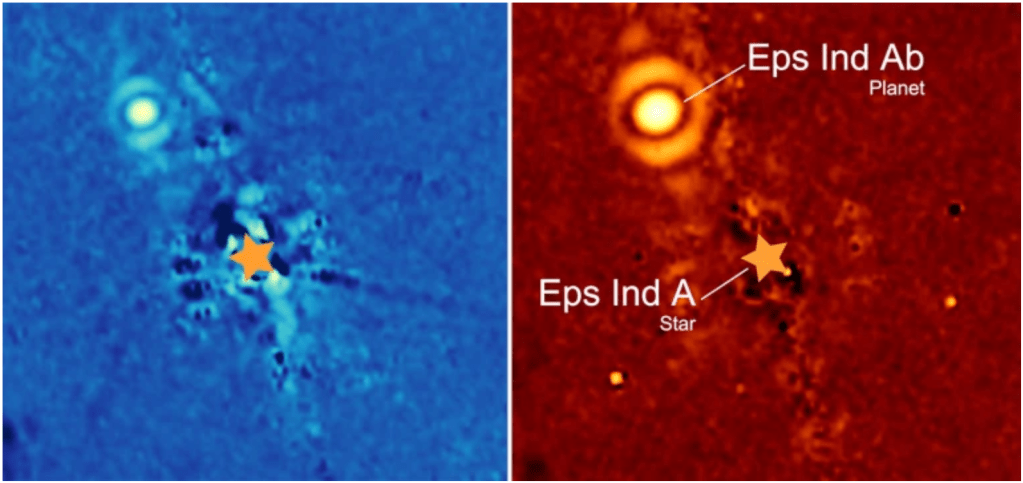

The first directly-imaged exoplanet was detected by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) just under two years ago, in September 2022, and the total number now stands at 25. It is important to note that these are images of exoplanets that had previously been detected by other methods, not new discoveries. Nevertheless, “photographing” such objects is a remarkable achievement and now a new record has been set for the dimmest (in infrared terms) planet ever imaged.

Picture credit: T. Müller (MPIA/HdA), E. Matthews (MPIA).

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02440-3

Lead author of the paper announcing the exoplanet image, Elisabeth Matthews of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, describes the planet as being “cold” and that is no exageration as its surface temperature is only just above freezing (275 K). This means there is relatively little heat generating the emitted light, resulting in a weak and long-wavelength signal that is particularly hard to detect.

Fortunately, there are three factors that alleviate this challenge;

- Firstly, the host star (ε Indi A) is relatively nearby – about 12 light years from the Sun.

- Secondly, the planet (ε Indi Ab) is categorised as a “giant Jupiter” and is estimated to weigh six times as much as Jupiter itself.

- Thirdly, the planet is located three times further out than Jupiter is in our own Solar System, placing it at an equivalent distance mid-way between Saturn and Uranus.

It is this combination of closeness to Earth, large size and remoteness from the host star that has made imaging of the planet possible.

Although the planet’s properties suggest it is likely to be composed mostly of hydrogen gas, Elisabeth Matthews’ team will now undertake follow-on observations to measure the planet’s spectrum, hoping to reveal information about the actual composition of its atmosphere.

The abstract of the original article (A temperate super-Jupiter imaged with JWST in the mid-infrared, by E.C. Matthews, A.L. Carter, P Pathak et al, Nature (2024), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07837-8) is freely available but the full article requires institution access (or payment of an access fee). A summary is publicly available at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02440-3.