The earliest ways of generating light all involved heat, whether that meant setting a fire, burning a pitch torch, lighting a wax candle or heating a mantle using a gas flame. When electricity arrived, thoughts turned from creating light by chemical means to the possibility of using an electric current.

Initial approaches still involved the generation of both heat and light (initially in arc lamps and later using incandescent filaments) but German glass-blower Heinrich Geissler and physicist Julius Plücker were the first people to move things in a different direction.

Working in the 1850s, Plücker wanted to investigate the effects of magnets on light and Geissler had the expertise to create evacuated glass tubes that glowed when a high voltage was connected across two electrodes protruding into the glass envelope. Plücker was actually exploring the effects of cathode rays rather than light itself but Geissler’s work enabled the British scientist William Ramsay to discover neon as a new element in 1898 (winning him the 1904 Nobel Prize for Chemistry) and subsequently led to the development of neon advertising signs by Frenchman Georges Claude in 1910.

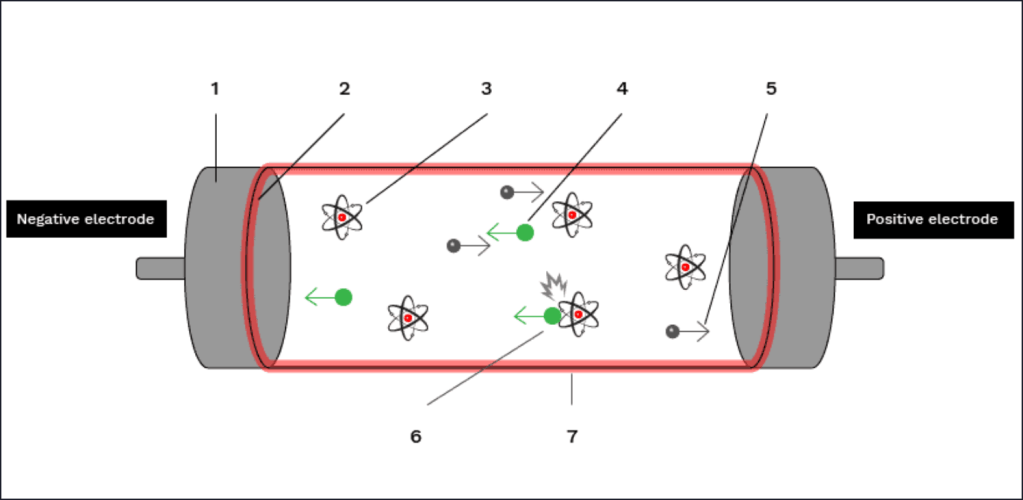

Although Claude’s original neon tubes emitted a bright red light, thanks to low-pressure neon gas inside, the term “neon tube” is now generally applied to all discharge lights of this type regardless of their gas filling. The mechanism by which light is generated in a discharge tube is explained in the diagram below.

It should be noted that diagram above is a “cold cathode” design, where a very high voltage is needed to ionise the gas in order to produce free electrons inside the tube. In “hot cathode” designs, thermionic electrons are released from a separate heater coil and are accelerated across the tube, colliding with neutral atoms as they race towards the positive electrode. As is the case for cold cathode tubes, it is these inelastic (energy transferring) collisions that cause electrons in orbit around neutral atoms to become excited and subsequently release a photon of light when they decay back down to their ground state.

In both types of discharge tube, the energy of the photon that is released exactly matches the electron’s change in energy. The fact that the photon has an exact energy means it will be seen as a specific colour of light. The connection between energy change (ΔE) and the colour of the light produced (frequency, f) is given by Planck’s equation;

where h is Planck’s constant and has a value of 6.63 x 10-34 J s.

The bright colours that make discharge tubes so attractive also make them poorly suited to general lighting because every illuminated object would appear to be a shade of the tube’s own colour. To avoid this problem, fluorescent tubes emit a mixture of colours that combine to give a neutral overall effect that approximates to “white light”.

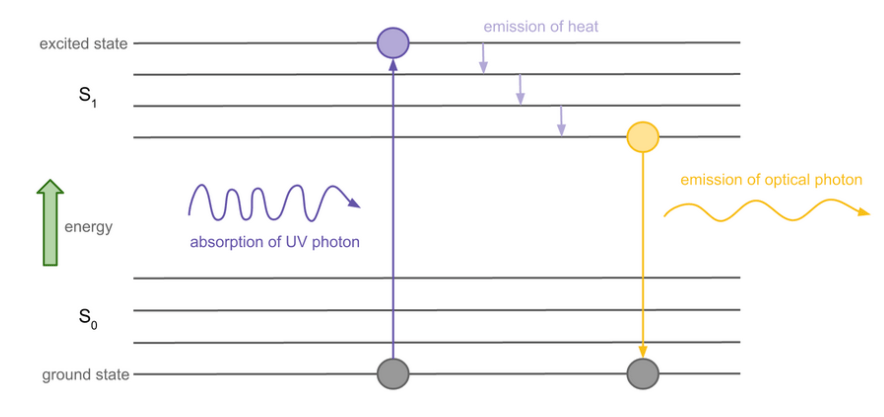

Fluorescent tubes employ a two-step process that begins with fast-moving thermionic electrons (produced by a hot cathode) undergoing inelastic collisions with atoms of mercury vapour. These collisions result in the thermionic electrons transferring some of their kinetic energy, causing the electrons orbiting the mercury atoms to be bumped up to a higher, excited, energy state. The excited electrons then fall back down to their ground state but rather than releasing visible light, as is the case in an ordinary discharge tube, they release invisible ultraviolet light instead.

The second stage of the process uses the fact that the inside surface of the fluorescent tube is coated with a powder that absorbs the ultraviolet photons. Some of the absorbed energy is transferred as heat but the remainder is released as a photon with lower energy than the incoming UV photon. The difference in energy for the incoming and emitted photons “converts” invisible UV photons into a specific frequency of visible light, as shown below.

In reality, the powder used in fluorescent tubes is actually a blend of different compounds so that the absorbed energy can be released in different ways, each of which produces a different visible colour and the combination of which gives a nearly-white overall effect.

FOOTNOTE: The explanation of fluorescence given here is a simplified version of what really happens and overlooks phosphorescence that also occurs in the powder coating: if you want more details about this then I strongly recommend an article on the excellent ChemistryViews website at https://www.chemistryviews.org/details/education/10468955/What_are_Fluorescence_and_Phosphorescence/. Similarly, if you want to learn more about real-world discharge lights then take a look at the article on High Intensity Discharge (HID) lamps on the LEDwatcher website at https://www.ledwatcher.com/high-intensity-discharge-lamps-explained/.

One thought on “Discharge and Fluorescent lighting”