How does the nucleus of an atom stay together? Why don’t the positively-charged protons repel each other and cause the nucleus to disintegrate?

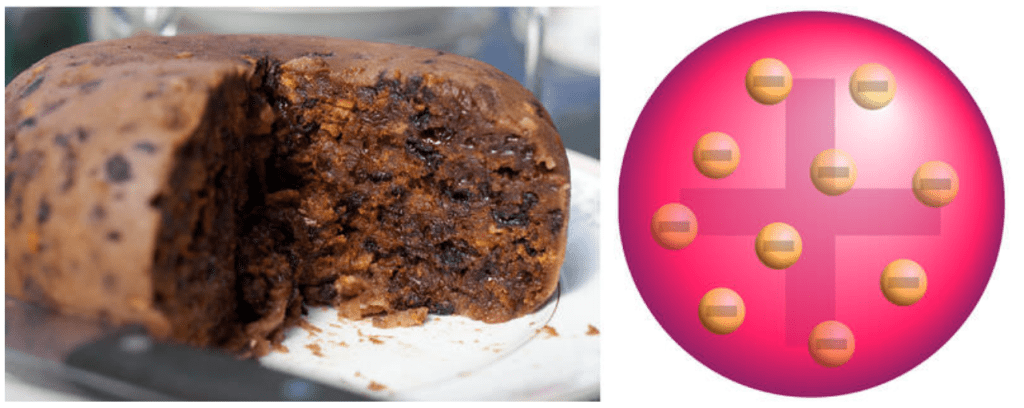

The early models of the atom imagined solid spheres, perhaps with different sizes, shapes or “colours” distinguishing one type of atom from another. Then came J J Thomson’s discovery of the electron in 1897 and suddenly atoms contained smaller (sub-atomic) particles that carried a negative electric charge. Given that atoms as a whole carry no overall charge, there also had to be positive charges in the atom to “neutralise” the effect of the negatively-charged electrons. This led Thomson to announce his “plum pudding” model of the atom, which proposed that the negatively-charged electrons must be embedded in a positively-charged substance.

The plum pudding model had its own problems, not least of which was how electrons could ever be removed (for Thomson to detect them) given that they were surrounded by an equal amount of positive charge that would surely create a huge electrostatic attraction holding them strongly inside the atom. But the real problem came when Ernest Marsden and Hans Geiger, working under the guidance of Ernest Rutherford, discovered that the positive part of the atom was in fact quite separate from the negative part. In fact, the positive charges (protons) were found to be confined to a very small region, which Rutherford named the nucleus. (There is a separate post about this experiment and its results at https://physbang.com/2020/10/04/rutherfords-gold-foil-experiment/.)

It was to be another 20 years before James Chadwick announced his discovery of the neutron, in 1932. It seemed that the neutron might offer an answer to the stability of the nucleus if it was assumed that neutrons could “glue” the positively-charged protons together. But things are never so simple and the changes that occur during radioactive beta decay mean neutrons must be able to “turn into” protons – and the reverse is also possible: protons can turn into neutrons. In both cases, the change in charge is balanced by a beta particle that is emitted from the nucleus. When a neutron turns into a proton an electron is released (from the nucleus) and when a proton turns into a neutron a positron (anti-electron) is released.

The subsequent theory of quarks, which was developed by Murray Gell-Mann in the 1960s as a way to categorise the vast number of particles that were being created in particle accelerators, introduced new fundamental particles that could bond together in different ways. In particular, Gell-Mann’s theory modelled neutrons and protons as different combinations of the same two quarks, known as up and down. The up quark has an electrical charge of +2/3 and the down quark has an electrical charge of -1/3: neutrons and protons both contain three quarks and the up-up-down combination of the proton produces and overall charge of +1 whereas the down-down-up combination of the neutron produces an overall charge of zero, matching the electric charges of the two nuclear particles.

The fact that neutron and protons both contain up and down quarks raises an interesting thought: is it possible that neutrons and protons might be held together in an atom’s nucleus because they are able to exchange quarks – and this exchange activity constitutes an interaction that “binds” protons and neutrons together? This was the notion that was explored by Hideki Yukawa, who called his exchange particles mesons, referring to the fact that they had medium mass that was between the masses of an electron and a proton.

More specifically, Yukawa’s “bonding” mesons are pi-mesons, often abbreviated to pions and contain only up and down quarks, always in twos and always with one of the two being an anti-quark. The animation shown below, from WikiMedia, is an attempt to visualise how the interaction might work.

As it happens, we now know that atomic nuclei are not held together by the exchange of pions but rather by gluons, in a theory known as quantum chromodynamics, but the current theory might never have been developed if it were not for Hideki Yukawa, who rightly received the 1949 Nobel Prize for Physics in recognition of his ground-breaking theory of mesons. You can read more about Hideki Yukawa on the University of Osaka website at https://www-yukawa.phys.sci.osaka-u.ac.jp/en/yukawahideki.

2 thoughts on “Hideki Yukawa and Meson Theory”