Experiments are often used to confirm (or, more usefully, refute) particular ideas but their impact is limited by measurement errors that can compromise the results. The obvious answer is to reduce the uncertainties as much as possible but what do you do if this causes the result to move further away from the expected value?

Let’s consider a situation that is sometimes suggested to investigate specific heat capacity. The idea is that a known mass of metal is heated in boiling water, so that it achieves a temperature of exactly 100 ⁰C, and is then transferred to a beaker of room-temperature water. The maximum temperature reached by the room-temperature water allows the specific heat capacity of the metal to be calculated.

Photograph (c) Jon Tarrant.

Based on this brief outline and the apparatus shown in the picture above, what do you think are the likely sources of uncertainty in this experiment? Note that the red item supporting the left-hand beaker is an electric stirrer that uses magnetic coupling to rotate a bar in the water; the orange handset in the middle of the picture is an infrared thermometer. What are your thoughts about the sources of error that could come into play when the metal block is transferred into the room-temperature water in the left-hand beaker?

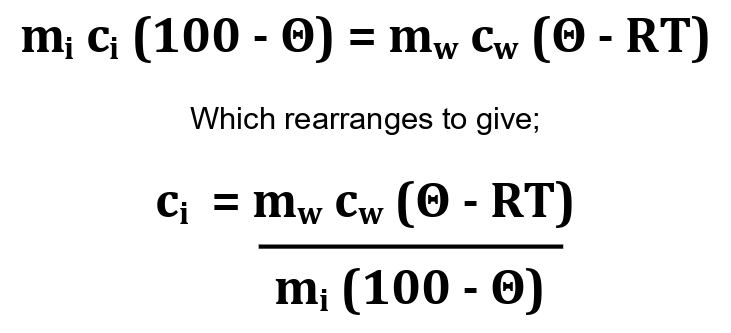

It may help to know that the specific heat capacity of the metal block is calculated as follows;

heat energy lost by iron block = heat energy gained by room-temperature water

Where;

- ci is the specific heat capacity of the iron block

- mi is the mass of the iron block (1 kg)

- cw is the specific heat capacity of water (4184 J kg-1 ⁰C-1)

- RT is the initial value of the room-temperature water (18 ⁰C)

- Θ is the maximum equilibrium temperature of the water

Which components in the equation are the most likely sources of error for the final result?

Measurements that are related to the right-hand side of the apparatus are fairly easy to analyse and the likelihood of errors is very small. The mass is a calibrated 1 kg block and the water is clearly boiling so it will have a known temperature of 100 ⁰C. The block was in the water throughout heating and remained there for five minutes once the boiling point was reached: this should have been sufficient to ensure that the iron block was in thermal equilibrium with the boiling water so it too had a temperature of 100 ⁰C.

The left-hand side of the apparatus is trickier. The mass of water was determined using a 250 ml measuring cylinder that was marked at 10 ml intervals. The volume used was 660 ml. The exact density of water at 18 ⁰C is 0.9986 g ml-1 according to US Geological Survey data (https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/water-density) giving a water mass of 0.66 kg. The uncertainty in the mass is determined by the resolution of the measuring cylinder, where +/- 5ml equates to +/- 0.005 kg.

The uncertainty in the maximum equilibrium temperature of the water varies depending on which measuring instrument is used. The glass thermometer gave a reading of 29 ⁰C (+/- 0.5 ⁰C) whereas the infrared thermometer gave a reading of 28.6 ⁰C (+/- 0.05 ⁰C). There is clear overlap between these two readings so we will use the glass thermometer’s measurement.

You might question this choice given that the infrared thermometer’s reading was not only more precise but also, perhaps, more accurate. Nevertheless, the glass thermometer was in situ throughout the experiment so also indicated the water’s initial temperature – and using the same instrument to measure both temperatures is a good way to eliminate any systematic error that may exist in the thermometer’s calibration. So let’s say the water reached a maximum temperature of 29 ⁰C (+/- 0.5 ⁰C) after the heated iron block had been lowered into it.

Substituting these values into the equation gives the specific heat capacity for iron as;

Completing the calculation reveals a final value of 428 J kg-1 ⁰C-1, which is fairly close to the expected value of 449 J kg-1 ⁰C-1 (according to https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/26/iron).

Although the discrepancy is fairly small, it is important to check whether it can be explained by the limitations of the experiment. An obvious place to start is the left-hand water beaker: this was not insulated so the maximum actual temperature could have been more than the maximum recorded temperature.

A possible suggestion for improvement might therefore be to lag the beaker and use a lid to reduce heat loss as much as possible but this might not be as important as first thought because the temperature of the beaker fell by only 1 ⁰C after the apparatus had been left standing for 10 minutes. This suggests that the rate of heat loss was very small and that adding insulation would probably have only a minimal effect.

So let’s look at the uncertainties in the recorded values, as collated below;

- mi = 1 kg (taken to be an absolute value)

- cw = 4184 J kg-1 ⁰C-1 (taken to be an absolute value)

- RT = 18 ⁰C (+/- 0.5 ⁰C)

- Θ = 29 ⁰C (+/- 0.5 ⁰C)

- The boiling point of water is taken to be 100 ⁰C as an absolute value

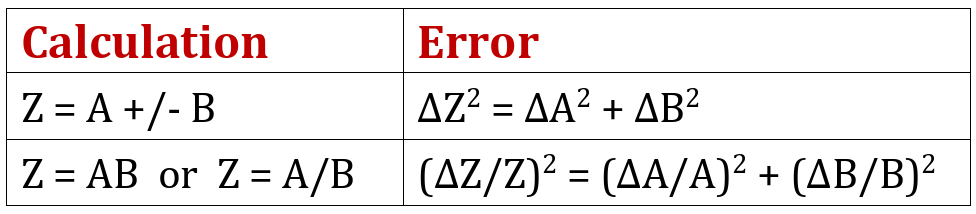

When values are combined, the resulting error is determined using the following rules (where Z is the final value and ΔZ is the associated error);

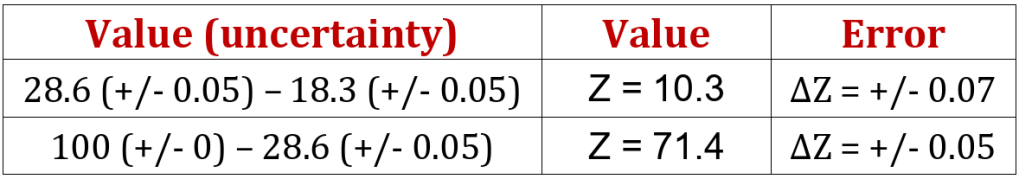

There are some other error rules too but these are the only ones we need to evaluate the current experiment. The best way to perform the evaluation is by dividing the calculation into separate stages, starting with the two subtractions shown in brackets, as indicated in the table below;

The only other value that is subject to an uncertainty is the volume of water in the left-hand beaker, which in turn gave the mass of water. Since the density of water was taken to be an absolute value, the error in the mass is the same as the error in the volume, giving 0.66 kg +/- 0.005 kg.

So for the numerator, the total error is given by;

Looking at the numbers involved, it should be obvious that the value for ΔZ/Z depends on the second term far more than on the first term: the calculated value for ΔZ/Z is in fact 0.0641 compared to 0.0636 for the second term alone.

In the case of the denominator, there is only one source of error and the ΔZ/Z value is therefore simply (+/-) 0.5/71, which gives the decimal 0.007 and again represents a much smaller uncertainty than that created by the measurements in the temperature rise of the room-temperature water.

The numerator and the denominator are divided so the final value for (ΔZ/Z) is found by taking the square root of the sum of the squares of the component values, giving 0.0645.

The final value for the specific heat capacity of iron was 428 so the associated uncertainty equates to +/- 28, giving a range of 400 – 456 J kg-1 ⁰C-1. Encouragingly, the reference value of 449 J kg-1 ⁰C-1 sits within the allowed range.

It is interesting to consider the extent to which using the infrared thermometer would have improved matters. Fortunately, not only was the water’s maximum equilibrium temperature of 28.6 ⁰C (+/- 0.05 ⁰C) recorded but so too was its initial temperature, which was 18.3 ⁰C (+/- 0.05 ⁰C).

Substituting these values into the equation for the specific heat capacity of the iron block generates a value of 398 J kg-1 ⁰C-1, which is not only lower than the first estimate but also below the lower limit of its range of expected values! But what about the uncertainty in this new value, given that the infrared thermometer’s measurements had a resolution that is ten times better (smaller) than the glass thermometer’s?

Repeating the error analysis given above now generates the following results;

In this case, the numerator error contains two similar uncertainties ;

This gives a value of 1.04 x10-4 and is added to the square of the denominator error (0.05/71.4): the result is then square-rooted to get 0.0102, which gives a range of +/- 4 in the answer of 398 J kg-1 ⁰C-1, corresponding to a range of 394 – 402 J kg-1 ⁰C-1. You will notice that the new range excludes both the value calculated using the glass thermometer’s measurements and also the reference value.

Sometimes in physics, improving the resolution of measurements can appear to make the result “worse”! (For a real-world example, check out Dr Becky’s excellent video on the current crisis in cosmology at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hps-HfpL1vc.)

In our experiment, the new result with higher precision forces us to consider whether there are any other, previously unidentified, sources of uncertainty in this experiment. And indeed that is the case. Can you identify at least one of them?

If you’re not sure where to start, here’s a hint for one of the issues: consider how the measuring cylinder must have been used. (It’s not the most significant issue but it’s the one that is easiest to quantify.)

2 thoughts on “Experimental errors”