With only the final Physics paper left to be sat in the this year’s AQA Trilogy exams, you should now be giving your revision a final push. Magnetism and electromagnetism is a fairly compact stand-alone topic and is the ideal candidate for a quick refresher. The knowledge you need can be divided into six areas (or just four if you are sitting the Foundation Tier paper) so let’s go through the necessary content…

Firstly, you need to know about permanent magnets and induced magnets. The former are normally referred to as just “magnets” and are commonly bar-shaped but may also be curved, like a horseshoe, or flat to stick on a fridge door. Induced magnets are metal objects that become magnetised when they are close to a permanent magnet but lose their magnetism as soon as they are moved away. Common materials that can act as induced magnets are iron, cobalt, nickel and some steels. The fridge door is behaving as an induced magnet when a fridge magnet is attached.

As well as being attracted to permanent magnets, induced magnets have the ability to “conduct” magnetic fields. This can be demonstrated by taking a normal bar magnet and holding it 10 cm above a paperclip: nothing happens because the magnetic field is very weak at that distance. But if you hang an iron nail from the bar magnet so that its tip is very close to the paperclip, the paperclip will be attracted to the nail. Importantly, if you keep the nail still and remove the bar magnet from the other end, the paperclip will fall off. It is worth saying that this is an idealised situation and in practice you would probably find the paper clip will be held for a short time before dropping.

Secondly, you need to know about magnetic poles, which are the parts of a magnet where the magnetic field is strongest. Magnetic poles always come in pairs; a north pole and a south pole. If two magnets are brought together with the same poles facing each other (north-north or south-south) the magnets will repel each other: this will happen even before the magnets touch because magnetism is a non-contact force. If the magnets are brought together with different poles facing each other (north-south or south-north) the magnets will attract each other – and, once again, this happens even before the magnets touch.

Note that induced magnets always feel a force of attraction so if the iron nail mentioned above is hanging from the north end of the bar magnet, it must have an induced south pole at the top and an induced north pole at the bottom end, where the paperclip is attached.

Thirdly, you need to know about magnetic fields, which have already been mentioned but not yet explained. A magnetic field is the region around a magnet where another magnet (or a magnetic material that can become an induced magnet) will feel a force. The strength of the magnetic field decreases with distance and can be revealed by placing a magnet under a sheet of paper then sprinkling iron filings over it. The tiny pieces of iron will become mini-magnets and will join, head-to-tail (with opposite induced poles) to make lines that follow the magnetic field. Places where the lines are closest together are places where the magnetic field is strongest – and that will be at the poles of the magnet, as shown below.

The Earth has its own magnetic field and a compass reveals directions by lining-up with the Earth’s magnetic field lines. The needle in a compass is actually a miniature magnet. Using an unmagnetised piece of metal and relying on induced magnetism wouldn’t be sensitive enough for a compass and, in any case, the needle needs to have a right-way-around indicator to show which direction is North.

Magnetic field lines are loops that have a specific direction: they always leave a magnet from the North pole and return to the magnet at its South pole. To investigate the direction of a magnetic field, a small plotting compass is placed at different locations around a magnet on a piece of paper and the direction in which it points is marked. The points are then joined up and the resulting field lines are given arrows that point outwards from the magnet’s North pole and inwards at the South pole.

The method is illustrated below but be warned that the picture should be interpreted as showing one plotting compass in multiple positions. If you were to use lots of plotting compasses at the same time, their magnetic fields would interfere with each other and distort the shape of the magnet’s own field, so you would get an incorrect pattern.

Fourthly, and finally for the Foundation Tier paper, you need to know that magnetism and electricity are closely connected via the effect that we call electromagnetism.

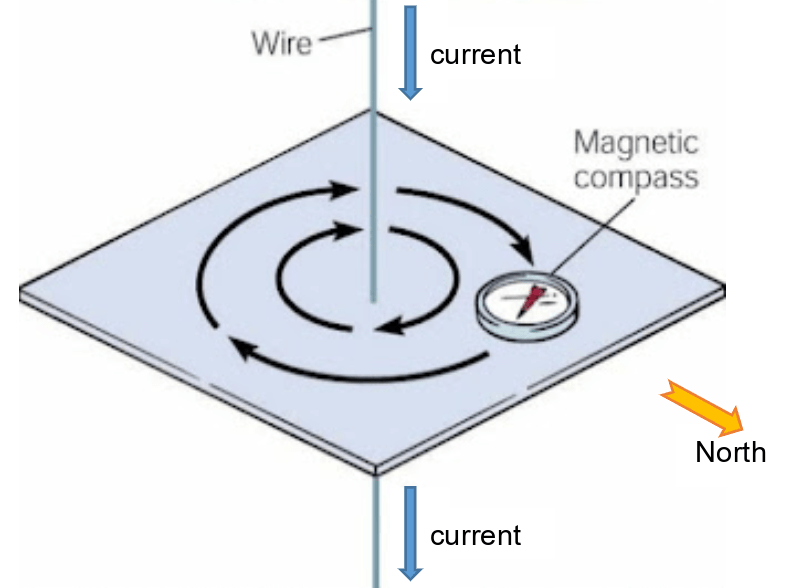

When a current flows through a wire, it generates a magnetic field that is strongest close to the wire and gets weaker further away from the wire. The magnetic field is circular around the wire. This can be demonstrated by placing a compass close to a wire with the circuit turned off then watching the compass needle deflect when the circuit is switched on. Obviously, the direction of magnetic North must be different from the direction of the wire’s magnetic field at the place where the compass is positioned if this deflection is to be seen.

Under normal circumstances the magnetic effect of a single current-carrying wire is fairly small but increasing the current will produce a bigger deflection and reversing the direction of the current will reverse the direction of the deflection.

To make the effect stronger, the wire can be wound into a coil. This is not too surprising if you think about a coil as a whole series of turns that are parallel to each other and going in the same direction. Using a longer the wire (and therefore putting more turns on the coil) will increase the strength of the magnetic field, the shape of which is very similar to that of a bar magnet. Inside the coil, there is a strong and uniform magnetic field, which is drawn as parallel lines that are close together. Inserting an iron core into the coil concentrates the magnetic field and makes its effect even greater. A coil with an iron core inside is known as a solenoid, which is the correct name for an electromagnet.

The direction of the magnetic field is predicted by what is known as the corkscrew rule, which says that if you curl the fingers of your right hand in the same direction of the turns of the coil and stick-out your thumb, your thumb will point towards the North end of the coil / solenoid.

Moving on to the Higher Tier content, the first extra thing you need to know is how to predict the direction and magnitude of the force that will be created when the magnetic field produced by a current-carrying conductor interacts with the magnetic field of a permanent magnet. The direction is found using Fleming’s Left-Hand Rule and the magnitude comes from an equation that is listed on the Physics Equation Sheet. At this point it is worth reinforcing the fact that forces are vectors so they need both a direction and a magnitude to be fully specified. I have written about Fleming’s Left-Hand Rule and the corresponding equation previously so please refer to https://physbang.com/2021/03/01/electricity-and-magnetism/.

The last piece of knowledge you need is the operation of a simple DC (direct current) electric motor, which works by the interaction of different magnetic fields when a current-carrying coil is allowed to rotate close to a pair of permanent magnets. There is a good summary of this on the BBC Bitesize website at https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zg43y4j/revision/4.