Radioactive decay is a random process. This means that if you were to observe a lot of unstable (radioactive) atoms, you would notice that they undergo nuclear decay at unpredictable moments.

But if you extended your observations for a longer period you would spot an underlying pattern. Although it is impossible to predict when one particular nucleus will decay, there is a time when half of the available nuclei will have decayed. This time is known as half-life and each different type of unstable nucleus has its own value of half-life.

The half-life for uranium-238, which occurs naturd ally on Earth, is approximately 4.5 billion years. Coincidentally, this is also the approximate age of the Earth. So when the Earth was formed, it contained about twice as much uranium-238 as we have today (because half of the original unstable nuclei have decayed by now). This also means the background radiation count due to uranium-238 has halved because if there are half the number of unstable nuclei remaining, there will be half the number of decay events still happening today.

Many half-lifes are much shorter than this;

- americium-241 has a half-life of 431 years. Am-241 is fitted in smoke detectors that can be used for many years without any loss in sensitivity. There is no danger to people in the room because Am-241 is an alpha source so none of the radiation can escape from the plastic case that houses the smoke detector.

- colbalt-60, which is used to sterilise medical equipment, has a half-life of 5.27 years

- one form of technitium, Tc-99m, is injected into patients for medical scans and can be used safely in this way because it has a short half-life of just of six hours. More importantly, Tc-99m releases only gamma radiation (this process is not covered in GCSE Physics) meaning that there is no danger of tissue damage for the patient who is being scanned.

- many of the highest atomic number elements have a half-life considerably less than a second, which explains why the search for new superheavy elements is so hard!

To see what half-life means in practice, let’s look at protactinium-234 as an example. Pa-234 has a half-life of 70 seconds so if you had 1.6 g of Pa-234 when you made your first measurement, the mass would have dropped to 0.8 g after 70 s had passed. The mass would then keep on halving every 70 s. So it would fall to 0.4 g after another 70 s, then 0.2 g after another 70 s, then 0.1 g after another 70 s, and 0.05 g after another 70 s and so on.

This pattern of halving the mass every 70 s will continue for a very long time because there are so many atoms in even a tiny speck of any material. In fact, just 0.05 g of Pa-234 still contains approximately 100 billion, billion atoms that are waiting to decay.

Graphs of nuclear decays always generate the same shape curve, regardless of which type of radioactive isotope is plotted. The illustration below illustrates this point. On the left is the specific curve for Pa-234, which has mass (g) on the y-axis and time (s) on the x-axis: on the right is the general curve, which is scaled in percentage for the amount and half-life intervals for the time.

The fact that the amount of a radioisotope present always halves during one period of half-life, allows you to calculate how much of a radioisotope would be left after a certain time – provided that you are given the starting mass (or radioactivity count) and the half-life of the material concerned.

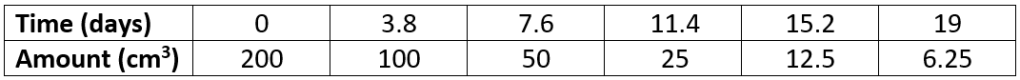

Let’s say that you start with 200 cm3 of radon-222, which is a radioactive gas with a half-life of 3.8 days. What volume of radon will remain after 19 days? You know the amount will halve every 3.8 days, so your working out (which should always be shown on examination papers) could look like this;

Note that the full amount is present at time zero (the start). It is a common mistake for students to think the full amount matches the first half-life, and therefore to finish with the wrong answer. But if you show your working, you will get the method mark(s) even if you make that common mistake.

Note also that in this case the amount was a volume whereas previously it was a mass. This doesn’t matter because “amount” can be measured in any appropriate way.

The level of radioactivity is also an indicator of the amount of radioactive material present. This means that if a Geiger counter starts off reading 6000 counts-per-minute and three days later the count has fallen to 3000 counts-per-minute, the amount of radioactive material present must have halved, so the half-life for this material must be three days. Remember: radioactive decay patterns work for any type of “amount” so don’t be thrown by the units used.

The correct unit for the activity of a radioactive material is counts-per-second, which is called becquerel (Bq). So our sample with 6000 counts-per-minute actually had an activity of 100 counts-per-second, or 100 Bq. And after three days (one half-life) its activity had fallen to 50 Bq.

The idea of half-life can also be used in reverse. For example, if you are told that radioactivity level of a certain sample drops from 200 Bq to 25 Bq after 15 hours, you should be able to work out the half-life. You need to notice that 25 is one-eighth of 200, and ⅛ is the same as three steps of halving, so you need to find the step size that will go from 0 to 15 in three steps by adding the same amount (of time) in each step. The process is illustrated below.

Hopefully, you can see that the numbers missing from the boxes are lower multiples of five, so the half-life for this radioisotope must be five hours. Note that you would never be expected to name the radioisotope concerned!!!

Finally, we need to note a few points about the nature of radioactive exposure;

Irradiation is the process by which an object is exposed to the ionising radiation released by a radioactive material without any contact between the radioactive source and the material itself. In this situation, the object does not become radioactive. Irradiation can therefore be used safely to extend the storage life of foods (by killing bacteria) without endangering human life.

Contamination occurs when a radioactive material comes into contact with an object and leaves physical traces. In this situation, the object becomes radioactive and can only be rendered non-radioactive by thorough cleaning. Such cleaning may not be possible if the contact involves a radioactive substance being eaten, absorbed or inhaled.

Irradiation is bad but it is only a problem during the period of exposure. Damage may be done to living tissue during exposure (such as killing bacteria on foods) but as soon as the irradiation stops, no further damage can occur (so people who eat the food later are completely safe). Contamination is worse because the damage keeps on accumulating until all traces of the contamination have been removed.

To minimise the effect of irradiation, maximise the distance between the object and the radioactive source and minimise the time of exposure. And any operators who are nearby must wear lead-lined aprons or other protective clothing that will protect them by absorbing ionising radiation.

To minimise contamination, store radioactive materials in sealed containers use robotic handling systems and, in exceptional circumstances when human intervention is needed, operators must wear protective suits with self-contained breathing apparatus.

It is difficult to be sure about the exact effects of ionsing radiation on living tissue but there are general figures that predict the level of expected damage. The greatest debate is about low-level exposure. One approach says there is a threshold below which is radioactivity is safe – and that threshold is related to (but higher than) normal levels of background radiation. The alternative approach says there is no safe level but the effects become harder to measure when the exposure level is very low.

Scientists share their research about the effects of radiation on humans: this sharing allows for a process known as peer review, where scientists can check and comment on each other’s findings to ensure that the conclusions are correct.