Radioactive decay happens when an unstable nucleus changes into the nucleus of a more stable (different) element. We know that elements are defined by the number of protons in their nucleus so the only way for an atom to change into something else is by either increasing or decreasing the number of protons that it has in its nucleus.

It turns out that changes to the number of protons in a nucleus can happen in only two ways; either the nucleus will lose two protons (known as alpha decay) or it will gain one proton (known as beta decay).

The two protons that are lost in alpha decay do not leave the nucleus on their own: they are accompanied by two neutrons. The combination of two protons and two neutrons is known as an alpha particle. If you think back to the periodic table, you should recognise that a cluster of two protons with two neutrons is the same as a helium nucleus. Therefore, alpha particles are also known as helium nuclei (the plural of nucleus).

Note that an alpha particle is simply a helium nucleus: it is not a helium atom. An alpha particle has no electrons but it can capture electrons to become a helium atom. The electrons can be stolen from nearby atoms, turning those atoms into ions (because they have lost electrons) and making the donor atoms more reactive than they were before they were ionised by the alpha particle. And that explains why radioactivity, which is also known as ionising radiation, is harmful to living things. The process of taking electrons from atoms in living tissue makes the tissue more likely to undergo changes, including starting cancerous growths. This is why it is so important to minimise contact with radioactive materials.

Let’s look at the change that happens when an unstable nucleus loses an alpha particle. The number of protons left in the nucleus is two less than it was before and the total number of particles in the nucleus goes down by four. We can represent this change using atomic number and atomic mass values as shown below, where X and J represent undefined atoms (there are no elements with X or J symbols in the Periodic Table);

Rather than writing “alpha decay” over the arrow, we add a symbol on the right-hand side of the equation to represent the alpha particle. Our general equation now looks like this…

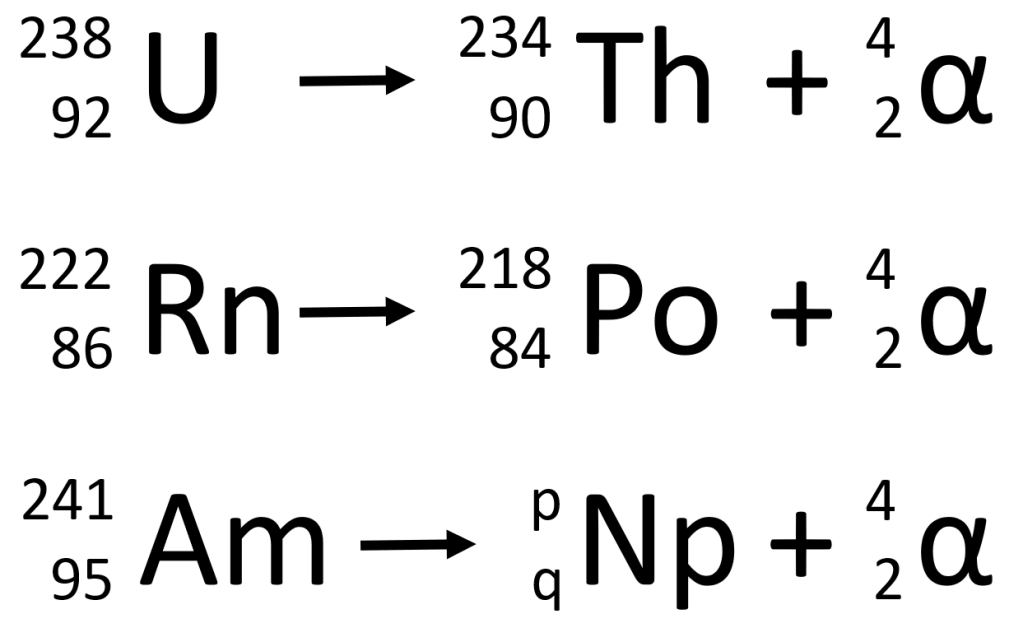

That’s the theory: here are some examples of what this looks like in practice…

In the first two examples, you should notice that the atomic mass on the left is the same as the sum of the atomic masses on the right. Similarly, the atomic number on the left is the same as the sum of the atomic numbers on the right. These facts can be used to deduce the values of p and q in the third example. Think about this for a moment. The principle involved here is an example of The Law of the Conservation of Mass and you should be able to explain why p=237 and q=93 are the correct answers for Np (neptunium).

In the other type of radioactive decay, beta decay, the nucleus gains one proton. This happens when a neutron “splits” into its constituent proton and electron. (Things are not quite that simple but this is the model we use for GCSE Physics.) The proton remains in the nucleus but the electron is ejected at very high speed and zooms past the orbiting electrons to reach the outside world, where it is called a beta particle.

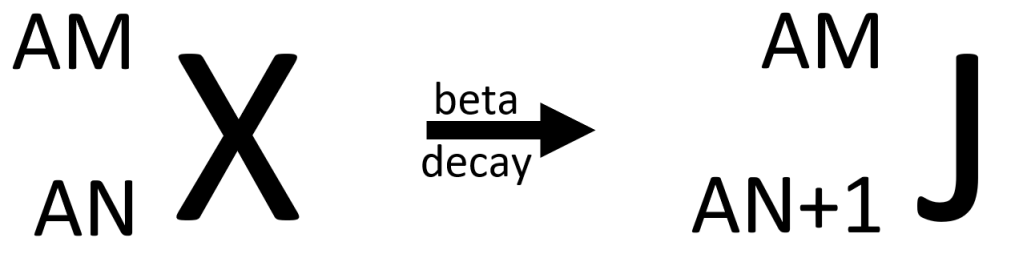

In beta decay, there is no change to the number of particles residing inside the nucleus (because the beta particle has very low mass and doesn’t count) so the atomic mass remains the same. But the extra proton means the atomic number must increase by one. The general equation for beta decay therefore looks like this…

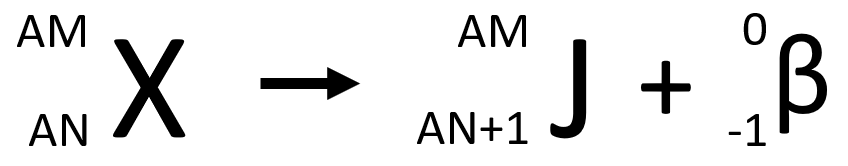

Once again, rather than writing “beta decay” over the arrow, we add a symbol on the right-hand side of the equation to represent the beta particle. The general equation for beta decay looks like this…

Note that the atomic number for a beta particle is -1. This is because atomic number counts how many protons are in the particle: a beta article has no protons but we can’t write zero as it has a unit of charge that is opposite to a proton’s charge, so we write -1. It may be tempting to call an electron an “anti-proton” but this is completely wrong because these two particles have different masses. In fact, the anti-electron is known as a positron and there is a special type of beta decay that will produce a positron – but that isn’t in the AQA Trilogy course so we won’t go into any further details here.

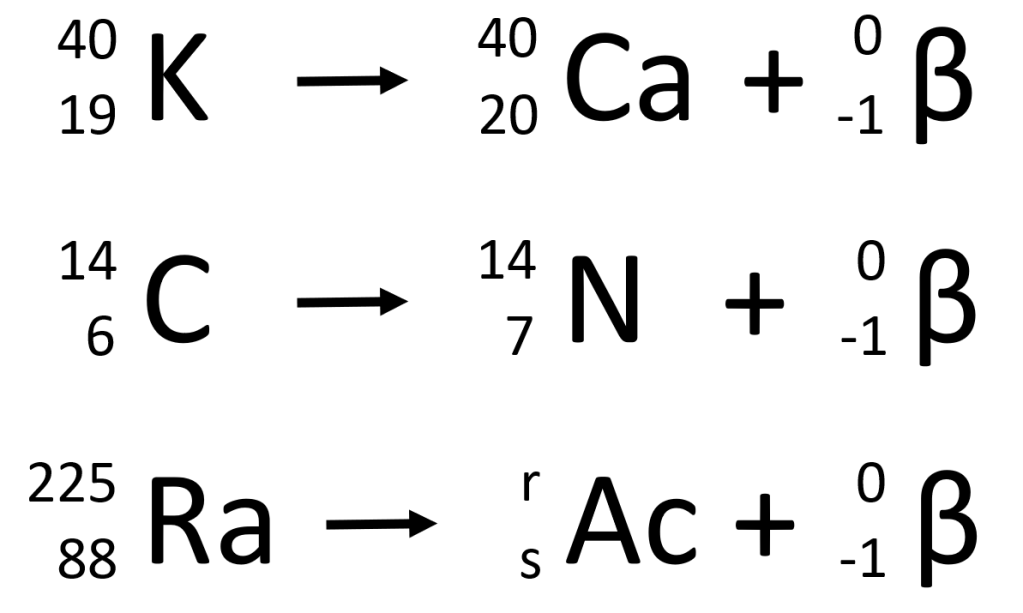

As before, we have some examples to show what beta decay looks like in some real nuclear equations.

The Law of the Conservation of Mass applies for beta decay in the same way that it applies to alpha decay. The atomic mass on the left of the equation is the same as the sum of the atomic masses on the right. And the atomic number on the left is the same as the total of the atomic numbers on the right. Notice that the atomic numbers include a negative value, so this particular addition is effectively a subtraction in beta decay. Using these facts, you should be able to work out the values of r and s in the third example shown above. Pause and think about this for a moment. The correct values are r=225 and s=89. Make sure that you can explain why these are the right answers!

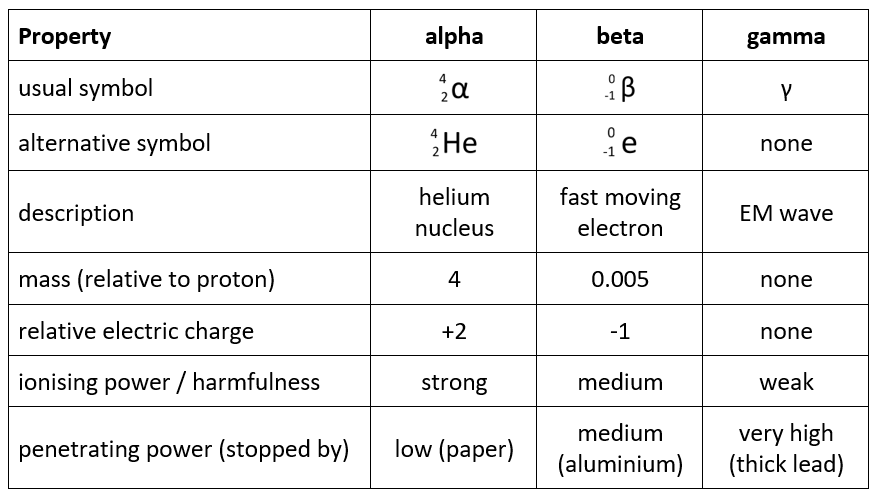

There are three more things you should know about nuclear decay equations. The first is that although people often use the Greek letters α and β to represent alpha and beta radiation, sometimes people use alternative symbols (see table) that you are also expected to recognise. The second is that there is another type of nuclear radiation, called “gamma”, but this is an electomagnetic wave rather than a particle and it has no effect on nuclear decay equations. The third is that neutrons can occasionally be released from the nucleus but this is very rare in natural radioactive decay and they have no ionising effect.

Everything you need to know about all three types of ionising radiation is summarised in the table below.

FOOTNOTE: There are also man-made radioactive decay processes (used in nuclear power stations) but the AQA Trilogy course does not cover these. Other courses take a wider view so you will find articles about (man-made) nuclear fission under the Radioactivity tab if you want to learn more.

One thought on “Alpha and Beta Nuclear Decay”