In a previous article, I recapped the key facts you need to know about atoms. Here we will look at the numerical information you need to remember and the concept of isotopes.

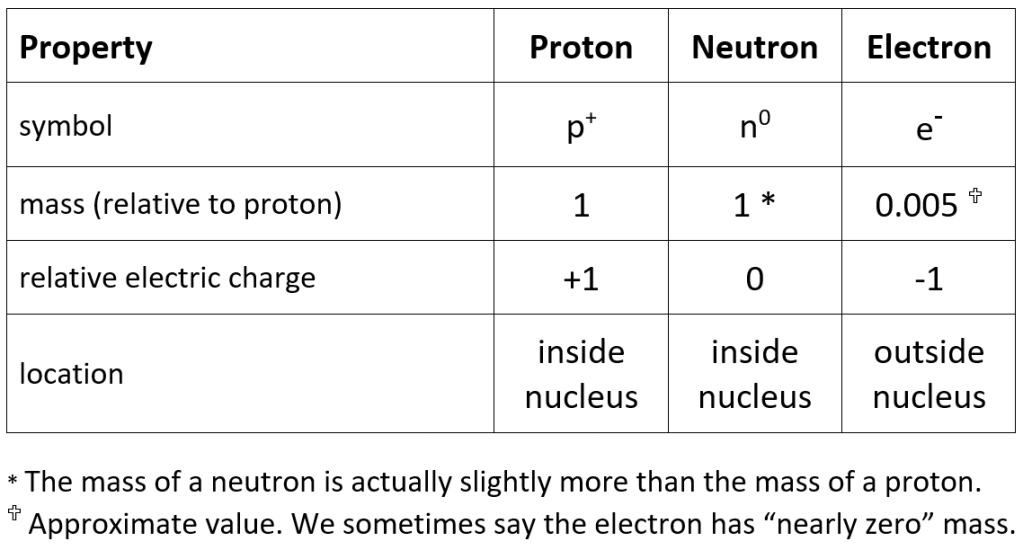

The table below lists the essental information you need to know about the three sub-atomic particles; protons, neutrons and electrons.

There is an inconsitency in the way that GCSE courses present this information, which can lead to later confusion. The big issue concerns the mass of the neutron: in tables such as the one shown above, neutrons are normally listed as having the same mass as protons but it turns out that during beta decay (see next article) a neutron changes into a proton and an electron, which is then expelled from the nucleus. In other words, you can think of a neutron as a proton combined with an electron. This model fits the fact that a neutron has zero overall charge (because the positive charge on its proton is exactly balanced by the negative charge on its electron) but for the model to work the neutron must have slightly more mass than a proton. And that fact is usually overlooked in the tables of sub-atomic particles that are presented for GCSE Physics.

We characterise atoms using two figures; the atomic number and the atomic mass, as explained below…

atomic number counts the number of protons (positively charged particles) in the nucleus of the atom. This number is also equal to the number of electrons (negatively charged particles) that surround the nucleus. The number of positive charges is therefore equal to the number of negative charges: this ensures that atoms have no overall charge.

atomic mass is equal to the sum of the number of protons and the number of neutrons in the nucleus of the atom. It is common for atoms of the same element to exist in slightly different forms, all with the same number of protons (the same atomic number) but with different numbers of neutrons (different atomic masses).

From a physics perspective, we can say that atomic number determines which element the atom is and atomic mass determines which version of the element the atom is.

For example, all carbon atoms have six protons, so the atomic number of carbon is always six. But some carbon atoms have six neutrons (giving an atomic mass of 12) whereas other carbon atoms have eight neutrons (giving an atomic mass of 14). Different versions of the same element are known as isotopes. So carbon-12 and carbon-14 are two isotopes of carbon.

In shorthand form, we can identify every atom using the element symbol and two values; one for atomic number and the other for atomic mass, like this…

The atomic mass is always greater than the atomic number (except for hydrogen, when the values are both 1). Further examples are shown below in a screen-grab from an interactive exercise that I thoroughly recommend you try as a way to check your understanding of atomic number and atomic mass.

Let’s analyse an example: lead (second from left) has an atomic number of 82 so we know it has 82 protons in its nucleus. We also know there are 82 electrons around the nucleus because the atom must have equal numbers of positive and negative charges to ensure that it is electrically neutral overall. In the image above, lead has an atomic mass of 210. This means there is a total of 210 nucleons (protons and neutrons inside the nucleus). Since we know there are 82 protons, we can calculate that there must be 128 neutrons in this particular atom of lead.

Remember that atoms can have different numbers of neutrons and still be the same element. But if the atoms have different numbers of protons, they must be different elements. This is illustrated below.

The illustration above shows that oxygen (atomic number 8) can exist either as oxygen-16, with eight neutrons alongside eight protons in the nucleus, or as oxygen-18, with ten neutrons. Neon also has ten neutrons inside its nucleus (20 – 10 = 10) but that does not make it the same as oxygen-18 because neon has 10 protons, whereas oxygen has 8 protons.

GCSE Physics papers often include questions to test your understanding of atomic number, atomic mass and isotopes so make sure that you fully understand the content covered here. And if you want to find out more about isotopes then I thoroughly recommend the excellent interactive Periodic Table created by The King’s Centre for Visualization in Science at King’s University in Edmonton, Canada.

Footnote: The following information is definitely not required for GCSE Physics but it is an interesting fact… The extra mass of the neutron, compared to a proton, is slightly more than just the mass of an electron. In truth, beta decay isn’t a simple as “splittng” a neutron but rather involves changing one of the quarks inside the neutron – but that knowledge is far beyond what is needed for GCSE Physics!