There’s an old science joke: “you should never trust atoms because they make up everything”. And that’s true. Atoms aren’t liars (as far as I know) but they are the smallest parts of all substances. But what else are you expected to know?

Firstly, atoms are really small. The diameter of a typical atom is of the order of 10-10 m. To put this in context, if you look at the millimetre markings on a rule, you could fit about ten million atoms between each of the markings.

Scientists’ ideas about what atoms look like have changed through history and I’ve summarised that progression a couple of times before: you can read the articles here and here. You are expected to be able to describe the essential points of the ways in which atoms have been pictured over the years, so make sure you read at least one of these articles, or the CompoundChem explanation, which is home to the A History of the Atom poster that provided the diagram below.

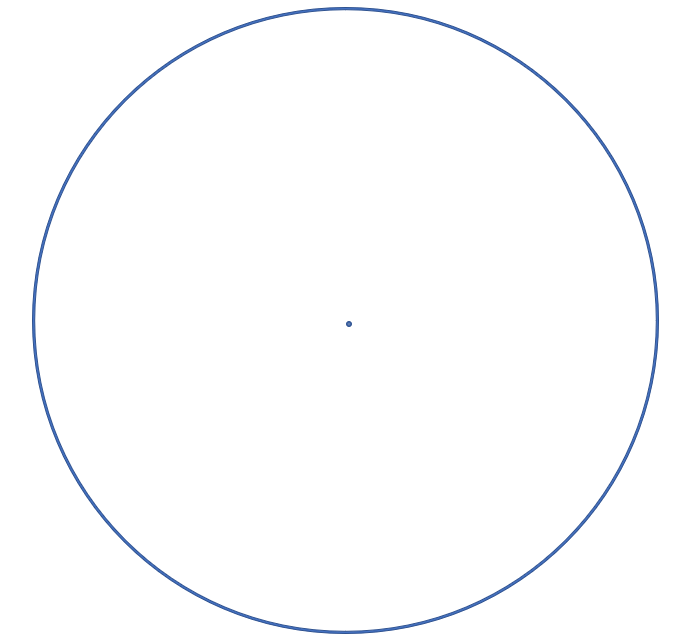

Although it isn’t the most modern form, we often draw atoms as shown in the diagram above, with a central positive nucleus and negative electrons arranged in concentric circles, known as electron shells, around the outside.

Diagrams like this are never drawn to scale. In particular, the nucleus is just a very tiny part of an atom and it is surrounded by a lot of empty space. For this reason, we often compare atoms to the solar system, with a small dense centre (the nucleus or the Sun) and lots of empty space containing smaller lumps of matter (electrons or planets).

In the Solar System, everything is held in place by gravity but inside an atom the attractive force is due to opposite electric charges. As shown in the diagram above, the nucleus has a positive charge and electrons have a negative charge so there is a force of electrical attraction holding these two types of particles together. The total positive charge in the nucleus is equal to the total negative charge of all the surrounding electrons added together, making atoms electrically neutral overall.

Electrons that are close to the nucleus experience a stronger attractive force and have less energy. If an electron were somehow given more energy then it would be able to move further away from the nucleus. And if it were given enough energy it could be separated from the nucleus completely. Obviously, I hope, electrons that are already further from the nucleus are the easiest ones to remove entirely. You should recognise that these facts lead to the idea of ionising an atom (in a chemical reaction) by the removal of one or more outer electrons, which are then “captured” by another atom to form an ionic bond.

It’s important to say that there are imaginary “steps” the electrons have to “climb” in order to move away from the nucleus. These are called energy levels and they sit between the electron shells. Something as simple as light shining on an atom can cause some of the electrons to jump up into the next energy level. But these intermediate “steps” aren’t stable so an excited electron will drop down again and release the energy it originally absorbed. Some GCSE courses include calculations about these transitions but this knowledge is not required for the AQA Trilogy papers.

Let’s go back to the nucleus: we know it’s small – but how small? The answer is that a nucleus is 10,000 times smaller than an atom. In absolute terms, the diameter of a nucleus is just 10-14 m (compared with 10-10 m for the entire atom). In the diagram below, an atom has been drawn closer to the correct scale and the nucleus is reduced to a tiny dot in the centre!

Despite its tiny size, the vast majority of the mass in an atom is located inside the nucleus. This fact was demonstrated by a famous experiment where sub-atomic particles (alpha particles) were fired towards a thin gold foil and their pattern of movement was observed. You need to be able to describe this experiment and explain how the information it revealed changed our ideas about the structure of an atom. There is more information about the experiment in this article.

I said earlier that the nucleus is positively charged and electrons are negatively charged – but there is a bit more to atoms than just these two oppositely charged particles.

Although electrons are fundamental particles (they don’t contain any smaller particles inside) the same is not true of the nucleus, which has both positive particles (called protons) and neutral particles (called neutrons) inside it.

I hope you might wonder how it is possible to pack a number of separate positive particles into a small space, given that they would all repel each other. The answer is the neutrons act like a kind of glue that holds the nucleus together. Things are actually a bit more complicated than that but this is a fairly good description for our purposes.

In the next article I’ll be looking at the numbers you need to know in order to be able to describe atoms in a bit more detail and after that we’ll recap the basic ideas of radioactivity.

One thought on “Atoms: Key Facts”