It is well known that darker surfaces heat up faster than lighter surfaces and reach a higher maximum temperature. But why? When the maximum temperature is achieved, there is a state of thermal equilibrium that is is due to a balance between the rates at which (new) energy is being absorbed and (previously) stored energy is being emitted. This is sometimes known as an energy budget because it is based on income and expenditure of thermal energy. Objects with a black surface will reach a higher temperature because they are better at absorbing energy (they have a higher thermal income) whereas white or silver surfaces tend to reflect more energy, so their stable temperature is lower. In all cases, the energy we are talking about is transferred as infra-red radiation.

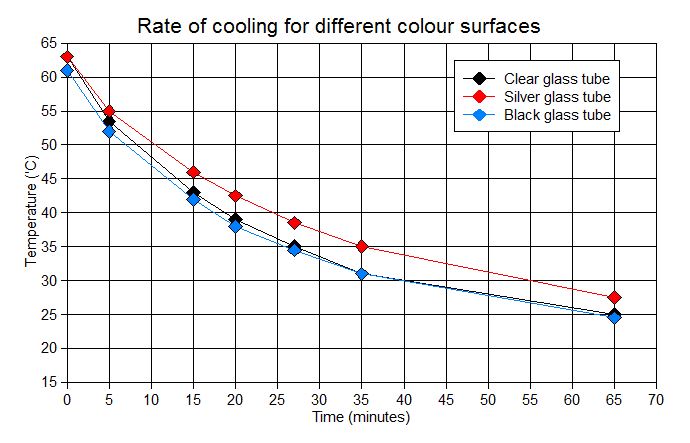

Perhaps surprisingly, objects with a black surface also cool down faster than objects with a white or silver surface. This means that white/silver objects tend to maintain a temperature that is both lower and more constant when the outside temperature varies. It is no surprise, therefore, that many buildings in Mediterranean countries are painted white to provide a more comfortable, stable, temperature inside.

There is a classic piece of physics apparatus that is used to demonstrate the fact that different surfaces radiate heat at different rates. You are expected to be familiar with this item, which was invented by John Leslie and is therefore known as Leslie’s Cube. The apparatus is a metal cube, typically about 12-15 cm, with different colour surfaces; matt black, glossy black, white and silver. The cube is usually filled with hot water and an infra-red thermometer is used to measure the energy that is emitted by each surface, as shown below. The matt black surface is found to be hottest and the silver surface is the coolest. (Note that if you were to touch the different surfaces of a Leslie’s Cube, they would all feel similarly hot because you would then be “measuring” thermal transfer through conduction, rather than by radiation.)

You are also expected to be able to describe laboratory experiments to investigate heat absorption (warming up) and heat emission (cooling down) for objects with different surface colours. These practicals are typically done using either tin cans or test tubes that have been sprayed to give either matt black or silver surfaces. The containers have water inside and thermometers are used to track the temperature changes. To improve the quality of the results, the containers need to be placed on insulating surfaces or held in clamps (to reduce heat loss due to conduction) and should be fitted with lids (to reduce heat loss due to convection).

The two graphs below are from experiments that demonstrate these effects.

Full details of the AQA Trilogy required practical to investigate the effect of surface colour on energy absorption and radiation are given in the Collins Lab Book, pages 93-96.

There are two common real-world examples that are used when discussing how the energy budget of an object determines the temperature of its thermal equilibrium.

The first example is a satellite, such as the International Space Station, that is strongly heated by direct sunlight and cools when it moves into the shadow of the Earth. Inside the ISS, it is important to maintain a steady, comfortable temperature for the astronauts. Highly polished shields are used reflect sunlight, thereby reducing the thermal income that would lead to very high temperatures, and black cooling panels that radiate excess heat into space. You can read more about these systems, and how NASA avoids the problem of the cooling water turning to ice in sub-zero temperatures, at https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2001/ast21mar_1/.

The second example is Earth itself, which is constantly receiving heat from the Sun during daylight hours and radiating heat into space at night. The Earth’s atmosphere traps heat and maintains a small temperature range that makes the Earth habitable. But changes on Earth, such as melting of the polar ice caps, modifies the Earth’s surface colour and therefore alters its energy budget. Reducing the proportion of surface whiteness will reduce heat reflection from the Earth, leading to more heat absorption. If that melting is produced by greater amounts of heat being trapped by greenhouse gases then it is clear that this could become an accelerating spiral leading to faster warming in the future, as well as weather changes prompted by different surface temperature distributions around the globe.

It is worth noting that the Moon, which is at the same distance from the Sun as Earth, has no atmosphere and its surface temperature varies by a colossal 300 °C, ranging from 127 °C in sunlight to -173 °C on the unlit side (https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/earths-moon/in-depth/). It is also worth noting that Venus, despite being further from the Sun than Mercury, is by far the hottest planet in the Solar System simply because the composition of its atmosphere has produced a runaway greenhouse effect, resulting in a mean temperature of 475 °C (https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/venus/overview/).