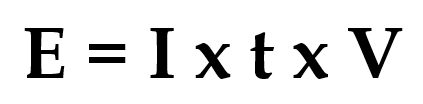

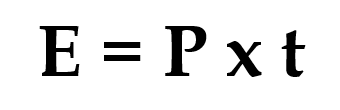

The amount of energy transferred in an electric circuit can be calculated by multiplying the current, time and potential difference. This is expressed in the equation given below.

Current is measured in amps (amperes), time is in seconds, and potential difference in volts. Remember that the symbol for current is the letter I – not C (see later below).

To understand this equation, you need to understand each part of it.

- Current is the flow of charge around the circuit. It is due to the movement of electrons, which are often shown leaving one side of the battery and travelling around the circuit before returning to the other side of the battery. The electrons are not “used up” in the circuit. This is easily demonstrated by inserting ammeters into the circuit immediately adjacent to the two sides of the battery: both ammeters show exactly the same value, proving that the same current (the same movement of electrons) exists at both “ends” of the circuit.

- Time is straightforward but must be converted into seconds if necessary.

- Potential difference is due to the energy change between two points in a circuit. This is why voltmeters must always be connected to two different parts of a circuit, such as opposite sides of a lamp. A high value of potential difference (high voltage) means a large amount of energy is being transferred in the part of the circuit that is between the voltmeter connections.

We often refer to potential difference as “voltage” but this is not correct: voltage simply refers to the unit of measurement for potential difference.

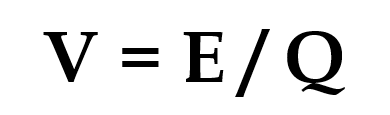

Potential difference has its own equation, where the symbol V is used for potential difference, although you may sometimes see the initials pd used in place of V;

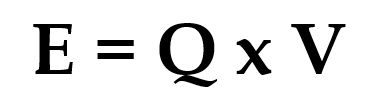

This can be rearranged to make energy the subject of the equation, as shown below.

In words, this tells us that the amount of energy transferred in an electric circuit is equal to the product of the charge that has flowed and the potential difference through which it has moved. If you have a good recall of circuit equations, you will know that amount of charge is calculated as the product of current and time: if that relationship is substituted into the equation above then you will return to the first equation listed in this article.

Remember that unit for measuring charge is the coulomb (C): note that the symbol C refers to the unit of charge whereas the symbol for the quantity of charge is Q.

If that seems like a lot of mathematics just to get back where we started then remember this one thing: potential difference defines the amount of energy that is carried by each unit of charge as the charge moves around the circuit.

The energy provided by the power source is transported around the circuit by the charge (electron flow, measured as a current) and transferred by electrical devices into other forms of energy. For example, lamps transfer the electrical energy as light, motors transfer it as kinetic energy (movement) and buzzers transfer it as sound (kinetic energy of the surrounding air).

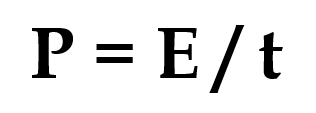

Electrical devices are normally described by their power rating, which is the amount of energy they transfer per second;

This too can be rearranged to make energy the subject of the equation, as shown below.

Small values of power are measured in watts (W): larger values are measured in kilowatts (kW) but must always be converted into watts (x1000) before performing any calculations. The energy transferred by a 2.5 kW kettle that takes three minutes to boil its water is calculated as follows;

The answer is 450 000 J, which can also be written as 450 kJ.

It is important that you can identify where this energy was stored initially, how it was transferred and where it is stored finally.

The energy came from the chemical energy store of the fuel that was burned to generate mains electricity (or from kinetic energy of the wind, or nuclear energy stored in radioactive uranium) and was transferred to the thermal energy store of the water (calculated using the water’s specific heat capacity, its mass and the temperature increase – probably about 80 °C, or 80 K if you prefer). This energy transfer was made possible by the charge flowing through the circuit, which carried the energy from the power socket to the heater.

Assuming that we have a perfect system (100% efficient) the amounts of energy at each stage in the process must all be the same; the fuel’s energy store reduced by 450 kJ, the circuit charge carried a total of 450 kJ and the heater increased the thermal store of the water by 450 kJ.

One thought on “Energy Transfers in Electric Circuits”