In the first part of this mini-series we looked at forces that act in exactly opposite directions. We noted that although these forces can be subtracted, the correct procedure is to combine the forces in more rigorous way that clearly takes account of both their magnitude and their direction. The most powerful way to do this is by using a vector diagram (scale drawing).

To illustrate the power of this method, we will now use a vector diagram to find the resultant of two forces that act perpendicular (at right angles) to each other.

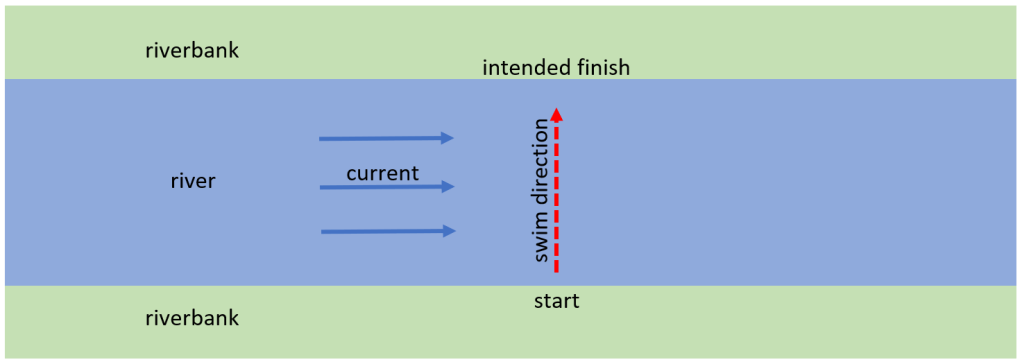

The situation we will analyse is a swimmer trying to cross a river with a current moving downstream, as shown in the diagram below.

The swimmer’s force, attempting to swim towards the opposite riverbank, combines with the sideways force of the current to produce a resultant force that moves the swimmer diagonally. The exact direction of the swimmer, and the overall force producing the diagonal movement, can be found using a vector diagram.

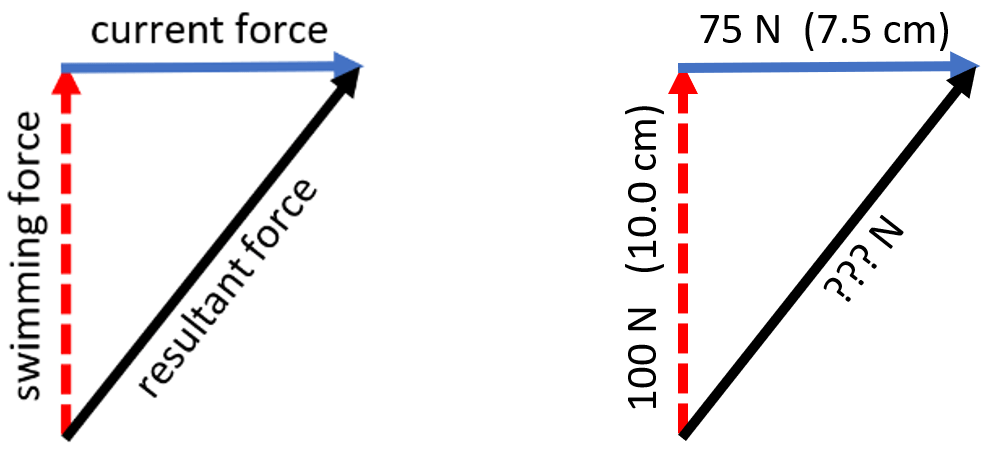

As explained in Part 1, the length of the lines used must be proportional to the magnitude of each force and the directions of the lines, indicated with arrows, must match the directions of the forces.

When the vectors for the component forces (swimming force and current force) are joined nose-to-tail, they create two sides of a right-angle triangle: the third side, the hypotenuse, is the resultant force, as illustrated below.

To find the resultant force, we choose a suitable scale and draw a right-angle triangle that has side-lengths based on the forces we are given. For example, if the current has a force of 75 N and the swimmer can exert a force of 100 N then the sides of our triangle could be 7.5 cm and 10 cm respectively. To find the resultant force, we simply measure the hypotenuse of the triangle (using a rule) and use the same scale to work out our answer in newtons. For example, if our measurement is 12.1 cm then our answer will be 121 N.

Mathematically-inclined readers will recognise that we can use Pythagoras’ Theorem to calculate the answer accurately. To do this, we square the two sides adjacent to the right-angle and add them together, then take the square root of the result. Even sharper readers will spot that this is a 3-4-5 triangle, so the resultant must have an exact value of 125 N.

To define the resultant force, which is a vector, we must also give the direction of the resultant. In GCSE Physics it is enough to say the direction is “diagonally to the right”.

If the question gives compass points, such as the swimmer is going North and the current flows from the West, you could say the resultant is 125 N in a North-East direction. (We do not need to use exact compass terminology as the mark in a GCSE Physics examination is given for the inclusion of any appropriate directional information.)

Again, mathematical readers will want to use trigonometry to calculate the angle of the resultant with respect to the swimmer’s intended direction: that’s great – but it is more than is needed to secure an exam mark at this level! (If you did the calculation, check that you got an answer of about 37°.)

In the final installment, we will look at forces that are at general angles to each other. Fortunately, the method of vector diagrams will still enable us to determine the resultant.