Let’s get the common misconception out of the way first: moving objects do not remain in motion because there is a force that keeps them going. In fact, it’s the opposite. Moving objects always remain in the same state of motion unless an external force stops them.

By “the same state of motion” we mean the same speed and the same direction – in other words, the same velocity. Conversely, if the velocity of an object changes then we immediately know there must be an external force acting on the object to produce that change. And since a change in velocity is the same thing as acceleration, we can state that whenever an external force acts on an object, the object will accelerate.

- If the external force is in the same direction as the object’s motion then the object will speed up and we say the object has positive acceleration.

- If the external force is in the opposite direction to the object’s motion then the object will slow down and we say the object has negative acceleration (also known as deceleration).

In summary… forces do not cause objects to move; forces cause objects to accelerate.

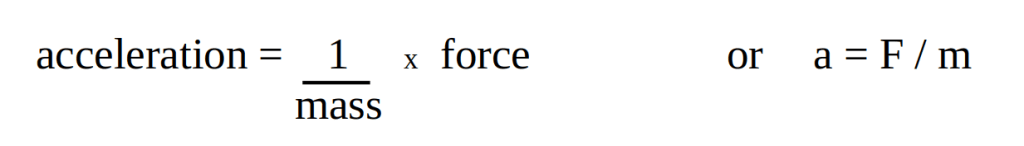

These facts are embedded in Newton’s Second Law of Motion, which states that the acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the external force acting on the object.

It turns out that the constant of proportionality is the inverse of the object’s mass;

This relationship tells us that if the same force is applied to two different objects, the object with the smaller mass will have the greater acceleration. That makes perfect sense in everyday life. If you were to give a sharp push on two shopping trolleys, one empty and the other fully loaded, I hope we would all agree that the empty shopping trolley would accelerate much quicker than the loaded trolley.

There is a required practical in the GCSE course that investigates this relationship by applying different forces to the same object and measuring the acceleration that is produced. We will look at this separately but before that I want to recap all three of Newton’s Laws of Motion.

- Newton’s First Law of Motion is as summarised at the start of this article: all objects continue in a state of steady motion unless they are acted on by an external force.

- Newton’s Second Law of Motion has just been explained: it states that when an external force acts on an object, the change in motion (acceleration) is directly proportional to the force and inversely proportional to the mass of the object.

- Newton’s Third Law of Motion says that when two objects act on each other, the force exerted by the first object on the second object is exactly equal and opposite to the force exerted by the second object on the first object. These two equal and opposite forces are known as a force pair.

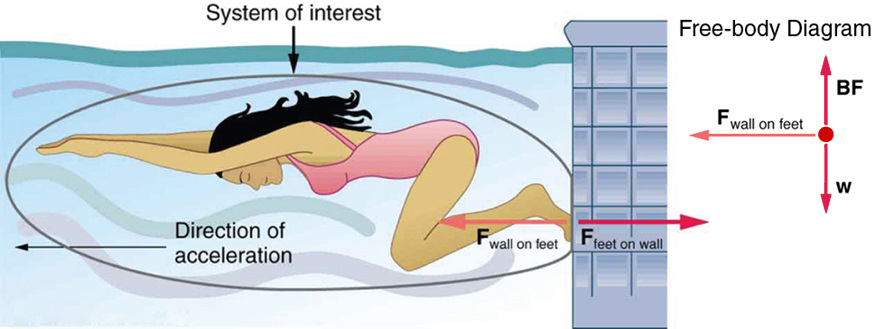

Newton’s Third Law is the hardest one to get right so let’s finish with an example, shown in the diagram below. A swimmer pushes against the wall (backwards) and it is the wall’s reaction force that acts forwards on the swimmer, causing her to move forward in the water.

Note that the swimmer moves forward because she pushes backwards and the structural strength of the wall provides a reaction force that acts forwards with equal magnitude and in the opposite direction to the force generated by the swimmer. In the free body diagram, we only show the forces that act on the swimmer (not the forces that act on the wall). Obviously, I hope, if we drew both the forwards and the backwards forces then these two would be balanced and there would be no resultant force to move the swimmer forward. Missing out the backward force is not “cheating”: it is the right thing to do because free body diagrams only show the forces acting on the object under consideration (the swimmer, in this case).