When a stationary object starts moving in a straight line, its motion can be divided into two stages. The first stage is when the speed of the object is increasing; the second stage is when the object has reached a steady speed.

We can rephrase these two stages using the word acceleration; the first stage is when the object has positive acceleration and the second stage is when the acceleration has fallen to zero.

If you were standing still and decided to start walking forwards, your period of acceleration would last for only one or two steps but if you were at the start of a sprint, resting on blocks, then you would accelerate for more steps and reach a faster maximum speed.

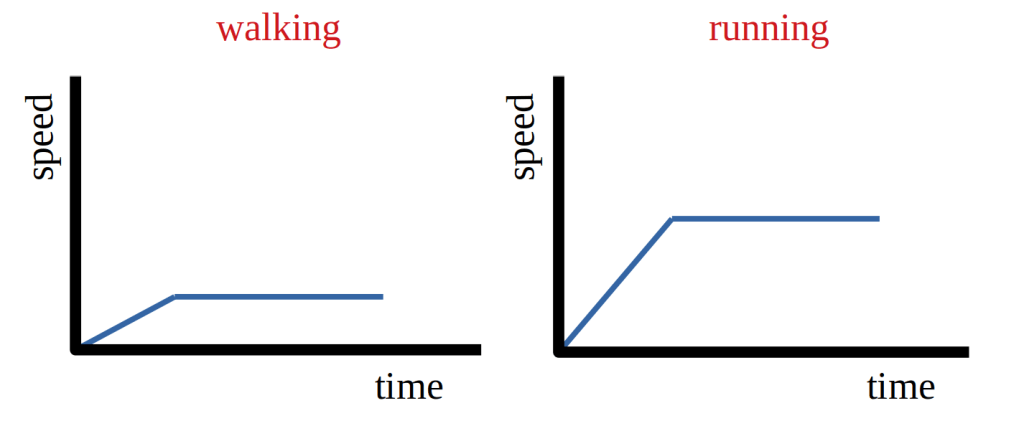

These two situations can be shown on graphs, such as in the illustration below.

It is important that you are able to interpret graphs of motion so let’s compare the two graphs shown above. We can make the following observations;

- there is a steeper diagonal gradient at the start of the running graph; this tells us that the runner has a faster rate of acceleration than the walker

- the horizontal section of the running graph is further above the x-axis; this tells us that the runner has a faster steady speed than the walker

- the total area under the running graph is greater than the area under the walking graph; this tells us that the runner has covered more distance than the walker in the same amount of time

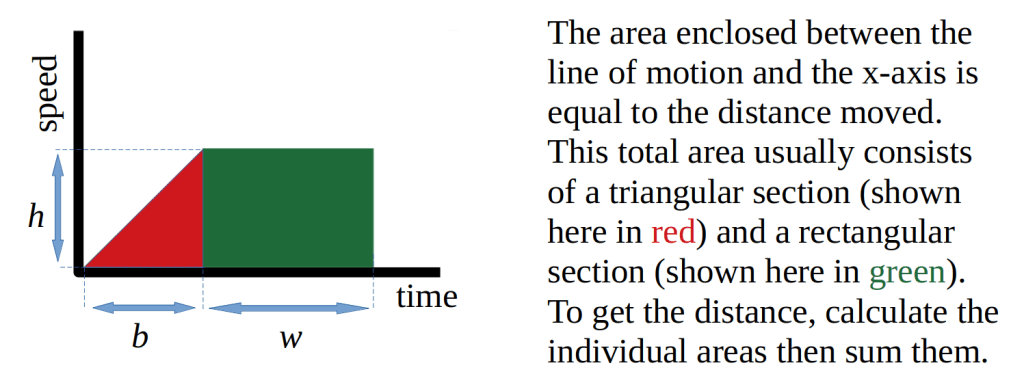

The third point above needs a little more explanation. You need to know that the area “under” a speed-time graph is equal to the distance moved. So if we measure the area that is contained between the line of motion and the x-axis, the value we obtain will be the distance travelled by the object.

This area is often composed of two sections; one triangular and one rectangular, as shown below.

The area calculations use standard equations that you should know. The area of a triangle is given by half of the triangle’s base multiplied by its height (½ x b x h) and the area of a rectangle is simply the width of the rectangle multiplied by its height (w x h). In an examination question, you may be required to read these values from a graph to determine the distance moved by the object. As always, make sure that you show your working in order to secure method marks in case you make an error in the final answer.

A trickier question might have a downward slope at the end of the graph. This would be the period when the object is slowing down and, if the graph were for a car, you could be asked to find the vehicle’s braking distance. The principle is the same: just find the area of the “slowing down” triangle and that will give you the answer you need.

I should point out that the sudden change from a sloping section to a horizontal line in the graphs above is completely unrealistic: graphs for GCSE Physics are drawn like this to simplify area calculations that allow us to determine the distance travelled on a speed-time graph.

In real life, there is a progressive transition between the two types of motion as the acceleration decreases to zero in order to achieve a steady speed. This is shown in the illustration below, which tracks Usain Bolt’s motion during his 100 m sprint at the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008.

https://www.wired.com/2012/08/maximum-acceleration-in-the-100-m-dash/

We have observed that a steeper line on a speed-time graph means a faster rate of acceleration. By making this observation, we have defined acceleration as the rate of change of speed. This is true but it is not the whole story.

To be more exact, we must define acceleration as the rate of change of velocity. You should recall that velocity is speed combined with direction. So an object will be accelerating when its direction is changing, even if its speed stays the same. This is the situation for an object that is moving in a circle, as discussed previously (Speed and Velocity).

In the next post, we will look at ways to measure both speed and acceleration in a lab situation.

One thought on “Speed and Acceleration”