Where does the idea of “absolute zero” come from? In part it stems from a need to avoid negative temperatures but a better explanation can be found by thinking about the kinetic theory of gases.

When a gas is heated, its particles gain kinetic energy. This in turn means that the particles have a higher average speed. And if a gas is cooled, the average speed of the particles decreases. It is therefore interesting to ask whether there is a temperature at which the average speed will fall to zero? And if such a temperature exists, then will it be different for different gases?

The problem, when it comes to answering these questions, is that we cannot observe the movement of gas particles directly (although we can observe it indirectly through Brownian motion). But we can measure other changes that are due to the change in average speed, such as the volume that a fixed amount (mass) of gas fills at different temperatures if the pressure is kept constant.

The change in volume can be seen qualitatively by placing a balloon over a rigid container, such as a conical flask, and watching the balloon partially inflate when the container is put into a bowl of boiling water. Similarly, the balloon will deflate to less than its normal (room temperature) volume if it is placed in a freezer. But these changes are quite subtle, even though the change in temperature seems fairly substantial.

To investigate this effect, we need a way of measuring the volume change accurately. A simple way to do this is by placing a narrow-bore (capillary) tube beside a scale. The tube is sealed at the bottom but open at the top and contains a “bubble” marker. Below the marker is a sealed volume of air and if the tube is heated (by being placed in beakers of hot water at different temperatures) this volume will expand, forcing the marker to move up the scale. Readings can be taken of the marker’s position at different temperatures and a graph can be drawn using these results. An example of this type of apparatus, which is available to schools at a very modest cost, is shown below.

The scale on the apparatus shown above is marked in millimetres (proportional to volume) but other types of apparatus can be marked directly in millilitres or cubic-centimetres (actual volume).

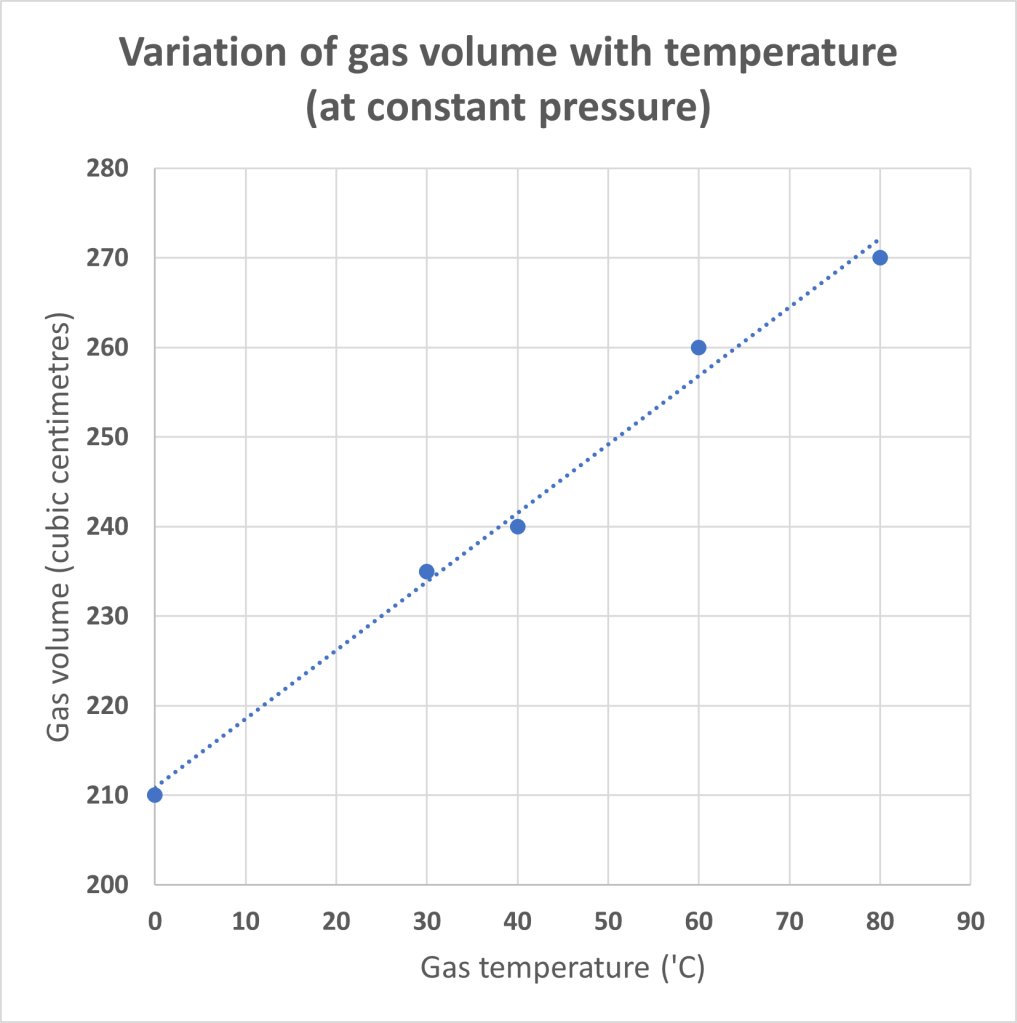

When the data collected from this sort of experiment are plotted, a graph like the one shown below will be obtained. (I will be honest and say that these aren’t real results that I’ve collected but the values are representative of what might be obtained in a real experiment.)

The graph reveals a good straight-line trend where the gradient of the line is approximately -0.767. This value is obtained by calculating (264-218) / (70-10) for the change in y divided by the change in x.

Given that the line has a y-value of about 210 cm3 at 0 °C, we can use the gradient to estimate the value of temperature that will reduce the volume to zero. The estimated value (given by calculating -210/0.767) is -274 °C.

In other words, the volume of the gas will be zero when the temperature reaches -274 °C and this will have been achieved because the gas particles have reached zero velocity. We know that because if the particles were still moving, they would have to occupy a definite volume to accommodate their movement. (Note that the particles still have what is known as zero-point energy, due to quantum effects, but in a classical sense the energy is zero.)

The name given to this temperature, where there is no movement of any particles, is absolute zero. By setting an actual zero at this coldest possible temperature, we ensure that all measured temperatures have positive values, which is reassuring for calculations in other areas of physics. It turns out that the true value for absolute zero is -273.15 °C, which is remarkably close to our estimated value of -274 °C.

This idea of absolute zero leads to a new scale for measuring temperature, called the Kelvin scale, where the zero value is equal to -273.15 °C. For convenience, the step size on the Kelvin scale is the same as the step size on the degrees Celsius scale, so temperature differences are identical on both scales. That is to say, the difference between 273 K and 293 K is the same as the difference between 0 °C and 20 °C, these being equivalent temperatures (if we ignore the .15 part of the value for absolute zero, which is normally the case).

In summary, by thinking about the kinetic energy of gas particles and its link to the temperature of the gas, we have been able to predict the existence of a temperature that corresponds with zero movement (let’s call it zero energy) of the particles. That in turn has given us a new scale for measuring temperature, known as the Kelvin scale, where the zero value is equal to -273 °C and the value of zero on the familiar Celsius scale is therefore 273 K. (Note that the scale is “kelvin”, not “degrees kelvin”.)

One thought on “Absolute Zero”