How long do you think it takes to get to cruising altitude on a long-haul flight? Aircraft travel has become so smooth that you could be forgiven for thinking that within 20 minutes, at the most, you’re in level flight. And you would probably also think that the aircraft’s speed is fairly constant from about 10 minutes into the flight. But neither of those assumptions would be correct. Here’s what I found on a flight from Vancouver to London, a few years ago.

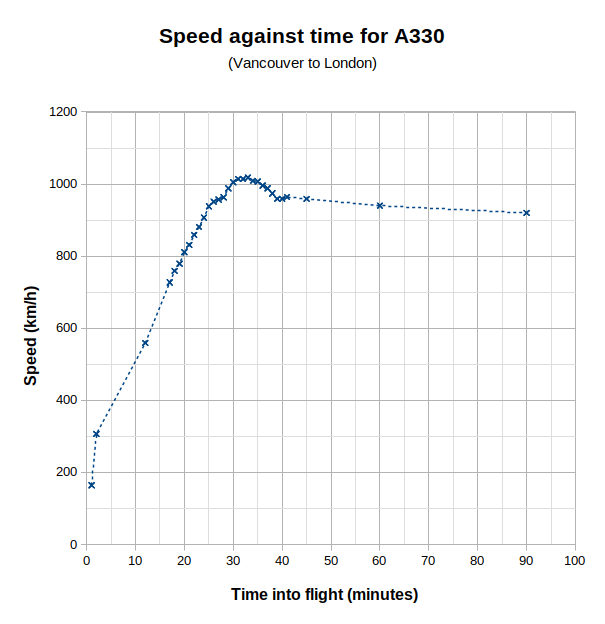

The two graphs below were created using information that was displayed on the journey tracking screen. Let’s start with the aircraft’s speed…

It is clear that the acceleration of the aircraft can be divided into four zones;

- First there is a period of high acceleration in the first two minutes, when the speed increases from zero (before take-off) to about 300 km/h.

- Next, there is an extended period of gentler acceleration that increases the aircraft’s speed to just over 1000 km/h during the next 30 minutes.

- Then there is a period of speed adjustment that is achieved by a significant negative acceleration that finishes about 38 minutes into the flight.

- Finally, the speed is trimmed to around 900 km/h in what I assume is a desire to achieve the optimum conditions for fuel economy and a punctual arrival. (The official cruise speed for an A330 aircraft is 870 km/h.)

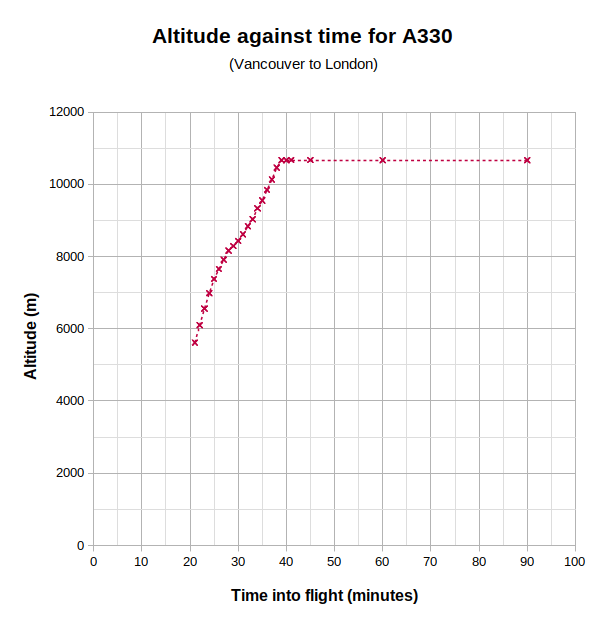

It looks to me as if the “hump” that can be seen between 28 minutes and 38 minutes might have been superfluous speed as the curve sections before and after this time look as if they should connect smoothly. But I suspect there are very sound aviation reasons why it’s better to “overshoot” the optimum speed and slow-down into level flight as the end of the “hump” coincides with the aircraft achieving its cruising altitude (see graph below).

This is less interesting but it does show, very clearly, that the aircraft maintained a constant cruising altitude of 10,670 m (about 35,000 ft) from about 38 minutes.

Apart from being an interesting data collection exercise, this information allows us to perform some calculations relating to acceleration. Let’s do this by looking at the initial climb, where the aircraft has greatest acceleration.

We must first ensure that we are using consistent units. The aircraft’s speed is given in kilometres-per-hour (km/h) but to get meaningful acceleration values we need to use metres-per-second, so our first task is to convert 300 km/h into m/s.

The easy bit is to convert 300 km/h into 300,000 m/h. We then need to divide by 3600, this being the number of seconds in an hour, giving 83 m/s.

The aircraft took two minutes, or 120 s, to reach this speed so its acceleration is given by 83/120, which equates to 0.7m/s/s (0.7 m/s2). That’s a very modest acceleration overall but it’s very likely that there was a higher initial acceleration as the aircraft picked-up speed travelling down the runway.

We can also estimate the force required to produce this acceleration, given that an A330 aircraft allows a maximum take-off load of around 220 000 kg and the product of the aircraft’s mass and acceleratin gives the force, which works out to be around 150 kN.

To investigate the initial acceleration further, I’m going to use my smartphone’s accelerometer to record some live data on my next flight – but that will be on a completely different aircraft running a short-haul route. I’ll post more information when it’s available.