Pressure explains why an applied force makes a drawing pin goes into the noticeboard and not your thumb: it also explains why a sharp knife is safer than a blunt one when practising culinary skills. There is also another aspect of pressure that relates to forces within a fluid (liquid or gas) and that is what we will be covering here.

Standing on the surface of the Earth, there is the entire weight of the atmosphere pushing “down” on you. We say “down” but in fact the atmosphere pushes on you in all directions – and that is a key fact that you need to know when we talk about pressure in liquids and gases.

A nice illustration of this fact is shown in the picture below. It is a packet of crisps that would normally have the usual “soft” feel when selected from a shop shelf but, when taken up a mountain, the packet looks as if it is about to burst open. Why?

Before we answer that question, there is a nice time-lapse video showing a crisp packet that went from swelling to bursting when a rally car drove up a mountain: you can view this video on the Red Bull website at https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/dakar-altitude-video-demonstration.

These two effects are both due to the fact that there is air inside the crisp packet and also air outside it. Standing in a supermarket, the air inside the packet and the air outside is all at normal atmospheric pressure. The bag hasn’t been filled with enough air to fully inflate the bag, so the bag feels soft.

Climbing to a higher altitude (the photograph and the video both show situations at about 3400 m above sea level) reduces the air pressure outside the bag but doesn’t change the air pressure inside the bag. As a result, there is less pressure on the outside of the bag pushing in than there is on the inside of the bag pushing out. This allows the air particles inside the bag to try to move further apart but they are held back by the bag itself, which becomes stretched and will eventually burst if the difference between the inside and outside forces becomes too much for the bag to resist.

To learn about this in more detail we need to get to grips with hydrostatic pressure, which explains the pressure in a static fluid. In other words, we’re not concerned about moving through a fluid, just being within one.

The key fact is this: hydrostatic pressure is a gravitational effect and is calculated by taking into account the following three factors;

- density of the fluid (which is assumed to be constant)

- gravitational field strength (usually taken to be 10 N/kg on Earth)

- depth under the surface of the fluid

The equation that combines these three factors is shown below, where ρ (the Greek letter rho) represents the density of the fluid, g is the gravitational field strength and h is the height (depth) under the fluid’s surface.

Standard SI units are used and the pressure is given in pascals (Pa) which are the same, numerically, as N/m2.

Importantly, even though the pressure is due to the weight of fluid above a certain depth, pressure does not act “downwards” but in fact acts equally in all directions, including upwards. This point has already been made in the context of the atmosphere and packets of crisps but it so important that it has to be mentioned again here.

Previously we have been able to predict whether an object will sink or float using Archimedes’ Principle, which states that an object will float if it is able to displace (push aside) a volume of water that has a weight equal to the weight of the object.

The maximum volume that can be displaced is equal to the volume of the object, and if the weight of that volume of water is less than the weight of the object then the object will sink.

We can summarise all of this by saying simply that an object will sink if its overall density is greater than the density of the fluid.

But why is that true? How does an object “know” its own density and the density of the surrounding fluid? More fundamentally, how does the object “know” how much fluid it has displaced – and therefore whether it should sink or float?

The answer can be found in the pressure equation, which deals with contact forces that are either balanced or imbalanced.

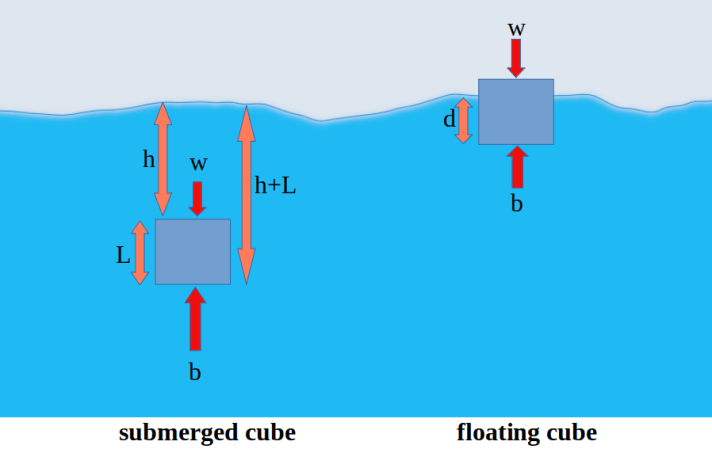

To keep matters simple, we will think only about a cubic object but the same ideas apply to all objects. The cube has side length L and the top surface is at a depth h below the fluid’s surface. This means that the bottom surface is at a depth of h+L so experiences a greater pressure than the pressure that acts on the top surface. This in turn generates an upward force called buoyancy, which acts in the opposite direction to the object’s weight. If the buoyancy is greater than the cube’s weight then the net force will be upwards and the cube will rise to the surface. But if the resultant force is less than the cube’s weight, the cube will move downwards (sink).

Assuming that it moves upwards, when the previously submerged cube reaches the surface it will float. The depth of the cube that is under the water line will be the depth required to give a pressure that generates a buoyancy force that is equal to the weight of the cube.

This sequence of events is illustrated in the diagram below.

One final detail to remember is that the pressure on the top surface of our floating cube is the pressure due to the atmosphere (not zero). That in turn means the pressure on the bottom surface is actually the pressure due to the depth of water plus the atmospheric pressure above he water surface. Since the components due to the atmosphere are equal we can cancel them out in our calculations but we cannot ignore the fact that they exist!

If you truly understand what has been discussed above then you will realise that the effect of atmospheric pressure acting on the top surface of our floating cube produces a downwards force but the effect of atmospheric pressure on the bottom surface is a force that acts upwards. This may seem illogical but it is true.

In the real world, objects are rarely cubes (a cubic ship would be unstable, difficult to steer and would generate huge water resistance forces when moving forwards) but the ideas remain the same even though the calculations are more complicated.

Footnote: You may ask why we have ignored the sides of our cube. The answer is that each side has an opposite face that sits at the same depth so the horizontal forces acting on the sides are equal in all directions.