Magnetism is a well known effect that was observed in nature thousands of years ago. In fact, the word “magnetic” comes from the region of Greece where materials that could attract and repel each other were first discovered: this region was called Magnesia.

The knowledge you need to have about magnets is very straightforward but this topic then extends into electromagnetism, which we’ll cover separately.

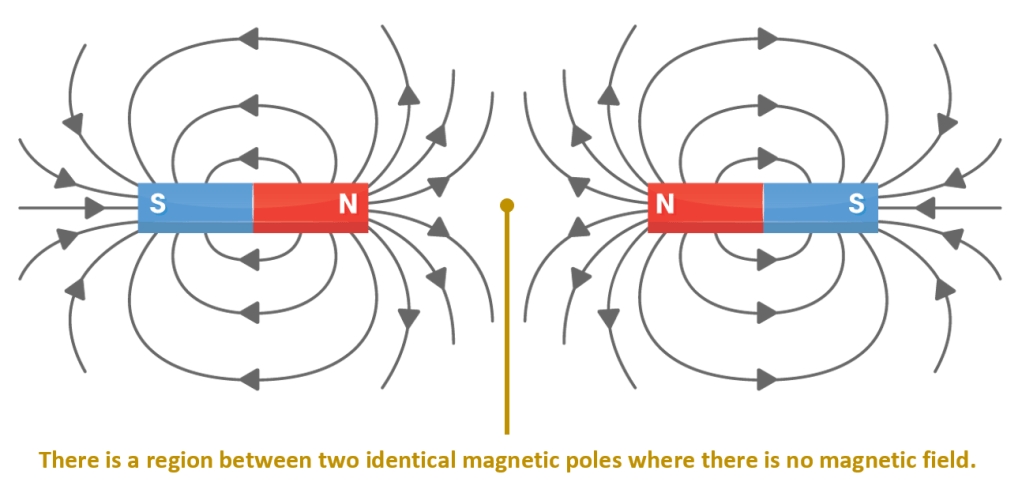

So let’s start with a quick recap of magnetic fields, which are instantly recognisable as those curved lines that are often shown around bar magnets. The diagram below is a typical example.

The lines show the strength and the direction of the magnetic field. Notice that the lines point away from the North pole and towards the South pole of the magnet. If you placed a magnetic object inside the field, it would feel a force. In fact, that is the definition of a magnetic field…

A magnetic field is a region of space where two magnetic objects will experience a force due to the interaction between them (at a distance).

In the case of a compass, its needle would turn to point along the field lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. The density of the lines (how close they are together) indicates the strength of the field and therefore the strength of the magnetic force in that region. You should be able to deduce that the magnetic force is strongest at the magnet’s poles because that is where the lines are closest together.

It is worth pointing out that although we draw these diagrams in two dimensions, magnetic fields are three-dimensional structures. JavaLab hosts a nice rotating animation that shows this: you can view the animation here. Note that the field lines are “dotted” so that you can see through them. You might need a while to work out what you’re seeing but it will be worth the effort!

Some GCSE Physics courses (but not AQA Trilogy) need you to know that the direction of magnetic field lines show the direction of force that would be experienced by a north magnetic monopole (an imaginary particle that has a north pole only). Full GCSE students should recognise this as being very similar to the definition of electric field lines, which show the direction of force on a positively-charged particle. There is more about electric fields in a previous physbang post, which you can read here.

Interestingly, there are some organisms that can sense magnetic fields. This isn’t part of any GCSE course but it’s an area of current research – and it can lead to some fun videos, such as this one showing bacteria doing line dancing!

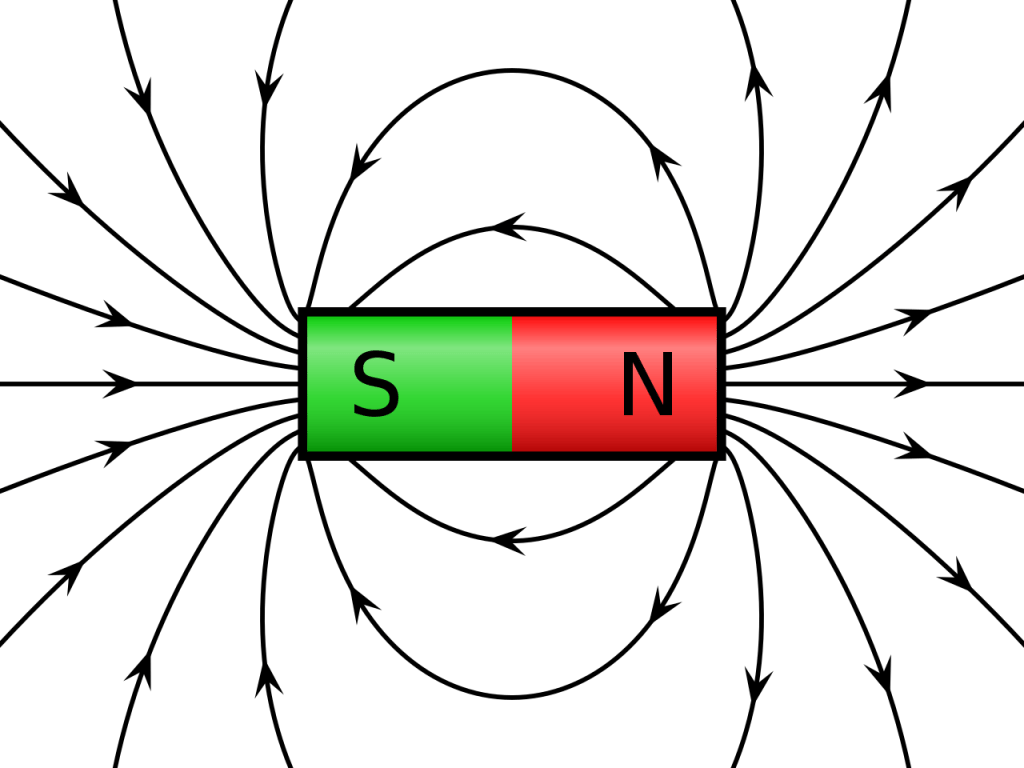

Getting back to what you need to know, it is important that you can recall and recognise the magnetic fields that are created when two magnets are brought close to each other.

- If the two magnets have opposite poles facing each other then the magnets will be attracted (pull towards each other).

- If the two magnets have the same poles facing each other then the magnets will be repelled (push each other away).

We explain these non-contact forces by considering the ways in which magnetic fields interact with each other.

When there are different poles facing each other, the lines of magnetic field that leave one magnet’s north pole can “blend” with the lines of magnetic field that are leading to the other magnet’s south pole. The field lines merge smoothly, without any sudden changes of direction, as shown below.

The fact that the field lines join together indicates that there is attractive force between the two objects. You should notice that there is a set of almost-parallel magnetic field lines in the region between the two opposite poles, with the lines curving outwards towards corners of pole faces. Moving further away from the facing poles, the magnetic field lines break away from the second magnet and turn backwards to link to each magnet to its own opposite pole in the usual way (as shown in the diagram at the start of this article).

Note that magnetic field lines are lines of force, and forces are vectors, so it is essential that magnetic field lines are always marked with arrows to show the direction of the force.

Rotating one of the magnets, so the identical poles now face each other, results in the two sets of magnetic field lines pointing in opposite directions. These forces act not only on an imaginary north monopole (as noted above) but also on the magnetic field lines themselves. There is even a region between the two identical poles where the magnetic field lines have completely repelled each other, meaning that there is no magnetic field in this central area, as shown in the image below.

That is all you need to know for your GCSE syllabus but if you want to learn more about magnetism and magnets then I strongly recommend browsing the Magnet Academy website, which has been created by the US National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, the largest magnet laboratory in the world. Although some of the content goes beyond what you need to know, there is a lot that I’m sure you will find interesting – not least the various interactive tutorials (located under the Watch & Play tab).

There is also some nice content on the Magnetman website, which you might find helpful.

Finally, there is also a great interactive animation of rotating magnets that I love watching: it is available at https://javalab.org/en/magnetic_force_en/. Very sadly, the field lines do not have arrows, which are essential for correctly labelled magnetic field diagrams in GCSE Physics – but it’s still a great animation.

2 thoughts on “Magnetic fields”