The facts and understanding that you need to have about springs is less detailed than it is for some other GCSE Physics courses. It is therefore important to use learning resources that are matched to this particular course. If you start reading about ultimate tensile stress, for example, then you are learning too much!

The first thing to remember is that there must always be a pair of equal and opposite forces acting on the spring for it to change its shape. If a single force were applied then the spring would simply slide across the table: you need a second force that opposes the first force in order to stop the spring from moving. Note that the force acting on the spring is not doubled just because there is a pair of forces: the second force is there only to ensure that the applied force changes the shape, not the motion, of the spring.

The change in shape is called a distortion (or deformation). In your course, the change in shape will always be a change in length, which can be either a compression (shortening) or, more commonly, an extension (lengthening). In both cases, what matters is how much longer or shorter the spring has become, not its actual length. To get the change in length (extension) you must subtract the starting length from the length when the force has been applied.

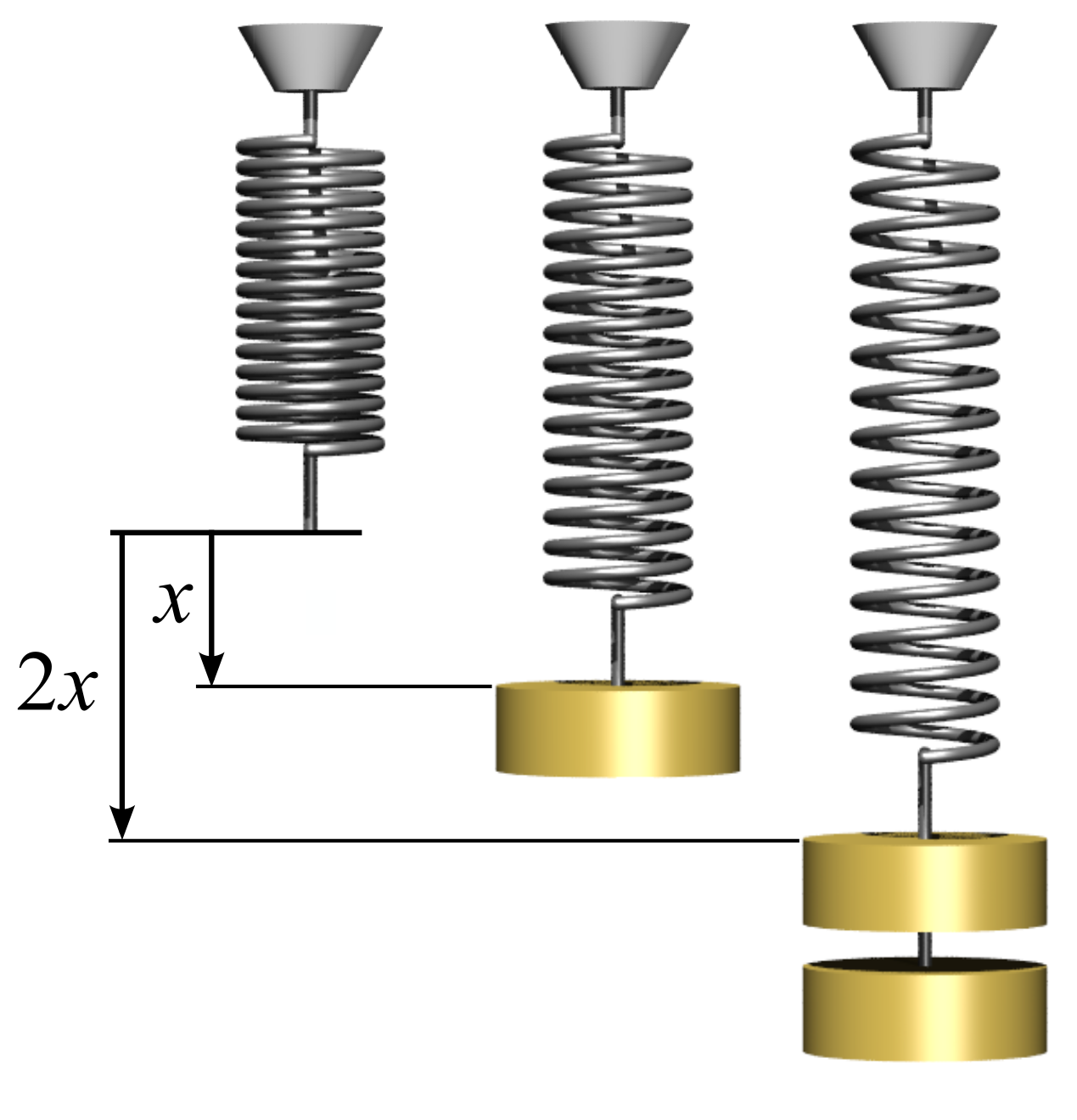

If you were to apply different forces to the spring and measure its extension then you would find a pattern in the results. A graph of extension (on the x-axis) against force (on the y-axis) would give a straight line that passes through the origin. This means the extension is directly proportional to the force and the relationship is known as Hooke’s Law. You don’t need to remember that name but you do need to be able to describe the pattern, saying something like: “when the force is doubled the extension is also doubled” – as illustrated in the diagram below.

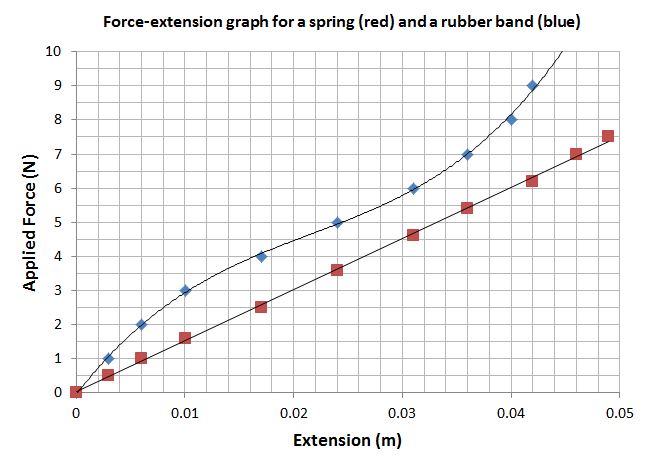

Not everything has direct proportionality between the force applied and the extension caused. In particular, graphs for rubber bands show a non-linear relationship between force and extension.

It is very important that you can describe the relationship shown in any example graph that may appear in the exam paper. This skill is no different to describing graphs that come up in other parts of this course: start by describing the linear part then state where the linear portion ends and describe what happens after that point – always referring to the variables on the two axes (never use inexact terms, such as “it”).

Look at the graph below and have a go at describing what it shows for the distortion of a spring and a rubber band. Be specific!

You must also know the difference between elastic distortion and plastic distortion;

- elastic distortion disappears when the force is removed (so the spring returns to its original length)

- plastic distortion remains after the force has been removed (the spring has exceeded its elastic limit and will no longer return to its original length)

Springs are intended to distort elastically and will always return to their original length when the force is reduced to zero (provided that they are not over-stretched). Other materials, such as lumps of clay, are intended to deform plastically so that they can be made into new shapes when a force is applied and the shape remains after the force is taken away.

There are two equations that you must be able to recognise and use – but you only have to remember one of them because the other will be included in the formula list at the back of the examination paper.

You must memorise the equation that links force and extension;

applied force (N) = spring constant (N/m) x extension (m)

F = k x Χ

The spring constant (k) is equal to the gradient of the line of best fit on a graph where force is plotted on the y-axis and extension is plotted on the x-axis. Although it is not good practice, you can also find the spring constant by dividing the force by the extension that it produces – but this only works because extension is directly proportional to force and it assumes that the values you use are on the line of best fit, which passes through the origin.

You must recognise the equation that links work done (energy) to the extension of a spring;

work done (J) = 1/2 x spring constant (N/m) x extension-squared (m)2

E = ½ k x Χ ²

Note that this equation only works when the extension is on the linear part of the force-extension graph – and that is the only situation for which you will be expected to do any calculations.

The energy stored is also equal to the area under the line in a force-extension graph. That is true regardless of whether the line is straight or curved. You should know this fact and be able to recognise that a greater area between the line and the x-axis means more energy is stored but you will not have to use it to get any numerical values.

To round-off your learning about springs, you must review the practical that you did as you may be asked about the method you used, including any improvements that could be made. You could also be asked to analyse or comment on typical results that can be obtained when carrying out this experiment.